Property

The Gift That Keeps Taking

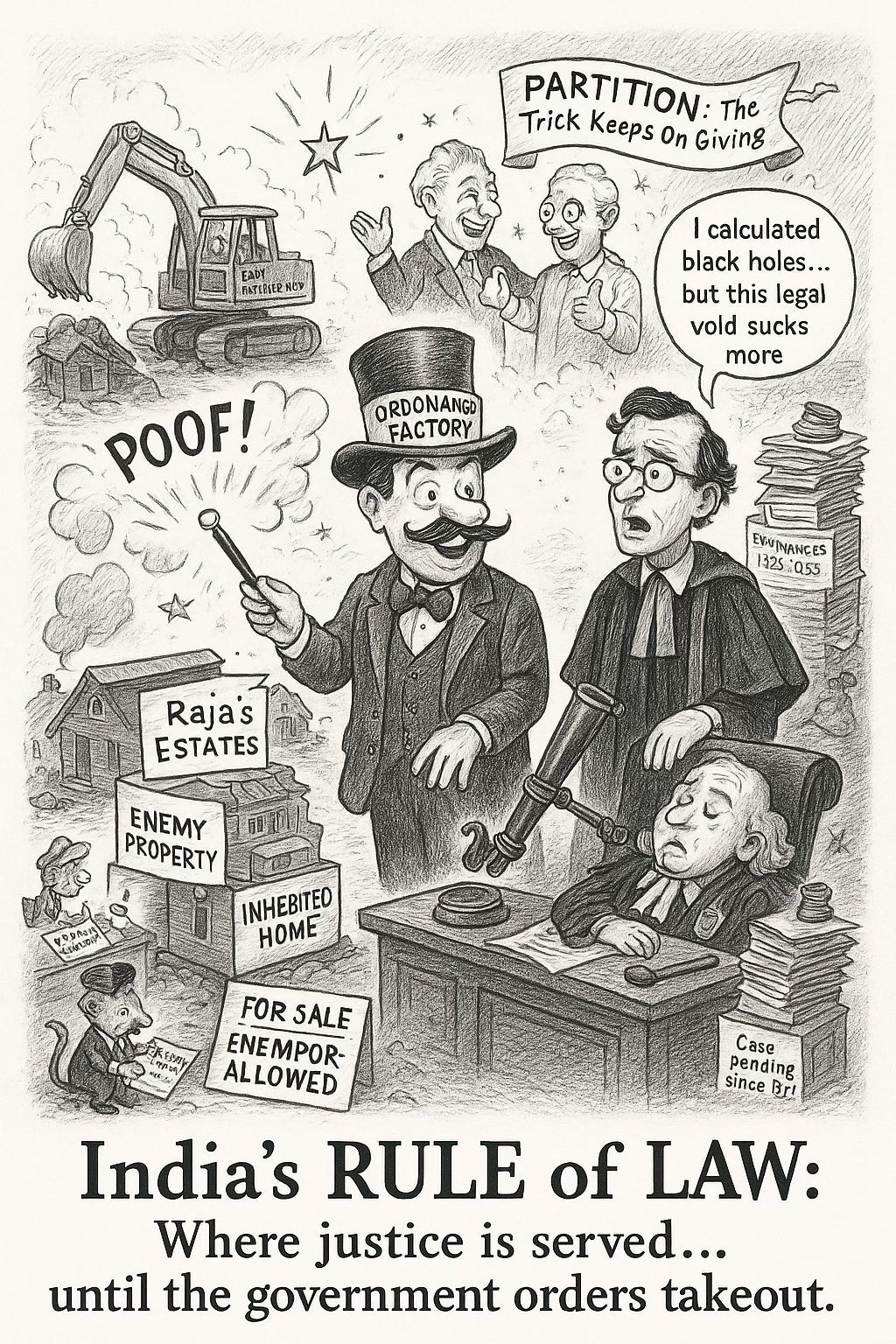

Picture this: October 2005. The Supreme Court of India delivers a landmark judgment. After decades of litigation, after the government seized properties under the Enemy Property Act because the owner’s father moved to Pakistan during Partition, the Court rules: These properties belong to the heir, an Indian citizen. The government must return them. Within eight weeks.

My mother led the legal team that won that case. She assembled it. They came on board because of her—because no other lawyer was willing to take on the government. She called in every favor from fifty years of practice. Put her reputation on the line. Other lawyers told her she was committing professional suicide to take on the state.

She did it anyway.

The Raja of Mahmudabad—whose father had been an associate of Jinnah but whose son remained an Indian citizen—finally had justice. Over 1,100 properties, nearly half of all “enemy properties” in India, would be returned. The Supreme Court was scathing: the government had held these estates “in a high-handed manner” for over 30 years. The Custodian of Enemy Property—a position that sounds like it was invented by Orwell—had to give them back.

My mother won the case everyone said was unwinnable.

For a brief moment, rule of law meant something.

Then the government did something so perfectly, quintessentially Indian that Kafka himself would’ve said “that’s too much, guys.”

They issued an ordinance.

Not a law. An ordinance—the constitutional equivalent of an executive sticky note, meant for emergencies like “Parliament’s not in session and Pakistan just invaded.” This emergency? A guy got his family property back after a court said it was rightfully his.

The ordinance, issued July 2, 2010, retroactively declared: “That Supreme Court judgment? Doesn’t count anymore. We’re taking the properties back.”

Public outcry. Opposition MPs from minority communities protested—since most “enemy property” claimants are Muslim families whose relatives went to Pakistan. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh withdrew the ordinance in August 2010. Democracy works! The bill was introduced in Parliament and then quietly allowed to lapse.

My mother had won. The system had worked. Justice prevailed.

Everyone was psyched.

Six years later, new government, same property grab. January 2016: Fresh ordinance. Parliament reconvenes and it expires after six weeks? Issue another one. And another. And another.

Five times. They issued the same ordinance five times through 2016.

Even President Pranab Mukherjee—whose job is ceremonial rubber-stamping—had “reservations.” He signed them all anyway. Because what else do you do?

Finally, March 2017: The Enemy Property (Amendment and Validation) Act passed Parliament during an opposition walkout. Made permanent. Retroactively. With full effect back to 1968.

The law now declared: - Legal heirs of “enemies” are themselves “enemies”—even if they’re Indian citizens

- Enemy property remains with the Custodian forever, regardless of death, citizenship change, or court rulings.

- Normal inheritance laws don’t apply.

- All courts are barred from hearing any cases about enemy properties.

- Any past transfers are void.

- The government can sell the properties and heirs get nothing

A Supreme Court judgment, erased by executive fiat repeated until it stuck.

Here’s the beautiful irony: The Raja of Mahmudabad who fought this case—Mohammad Amir Mohammad Khan—wasn’t some feudal landlord clinging to ancestral estates. He had a PhD in theoretical astrophysics from Cambridge. He taught at Cambridge and worked at the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste. He was an accomplished scholar in mathematics, a published poet in both Urdu and Persian, and a man who could discourse equally on quantum mechanics and Sufi philosophy.

And he came back to an India where this nonsense awaited him.

Where a Cambridge-trained astrophysicist had to spend decades in courtrooms because the government decided property law could be rewritten with the stroke of a presidential pen. Where the son of a Pakistan Movement supporter was deemed an “enemy” despite being born in India, raised in India, and serving as a Member of the Legislative Assembly in Uttar Pradesh.

The Raja of Mahmudabad asked pointedly: “Are we being punished for choosing to stay in India?”

He died in October 2023, at age 80, without recovering his inheritance. His Supreme Court victory had lasted exactly five years before being ordinanced into oblivion.

My mother’s legal triumph—won by doing what no other lawyer would do—became a Pyrrhic victory.

She’d spent five decades building a reputation for integrity. Taking this case risked all of it—losing meant professional embarrassment; winning meant making an enemy of the state. She did it anyway. And when the first ordinance came in July 2010, she wasn’t even surprised.

I remember her face when she read about it. Not anger. Resignation. She’d suspected this might happen. That’s what stung: she’d been right to be cynical, and that’s no way to live.

That’s what broke my heart: she’d been right to expect betrayal.

A Brief Interlude: Why I Live in Connecticut

You might wonder: With all these “connections,” with Modern School, Columbia University and a University of Texas education and a mother who argued before the Supreme Court—why Connecticut?

(And yes, my family were Zamindars on my father’s side. I know about this ridiculous system from both sides—the extractors and the extracted. Even Zamindars suffered from it eventually, which is its own special irony.)

This is why. Growing up in India, this is what I would have expected from the Indian government, and it is precisely what happened.

My mother won a Supreme Court case. India’s highest court ruled in favor of her client after decades of litigation. Properties restored. Justice served.

Then the government issued an ordinance nullifying the judgment. Not a law—an ordinance. A constitutional device meant for genuine emergencies: war, natural disaster, financial crisis. They used it to take back property a court said wasn’t theirs.

The Supreme Court refused to enforce its own judgment. That’s when we both knew. Not hoped. Knew. The fix was in.

She mentally gave up after the ordinances started. I could see it. But she kept fighting anyway, for the Raja, because that’s what you do when you take a case. You don’t abandon your client just because you’ve realized the system is rigged.

She died in 2016.

Finally, March 2017: Rammed through Parliament during an opposition walkout as permanent law. Retroactively. A Supreme Court judgment, erased by executive fiat repeated until it stuck.

She never saw the final betrayal. She was already gone. But she knew it was coming. We both did.

We’d argued about this for years. She believed in India. In its institutions, its courts, its constitutional framework. She’d devoted her entire career to that belief. I never did. Not once. I saw it with foreigner’s eyes—I had read enough Bertrand Russell and Milton Friedman and so things had become very clear to you. Even when I lived in India, I never believed the system would honor its own rules when power was at stake.

She thought I was cynical. Too Western. Too quick to dismiss what India had built.

I thought she was idealistic. Willfully blind to what the system actually was.

The ordinances proved me right. I wish likie hell they hadn’t.

She died still fighting for the Raja, but no longer believing in the system she’d spent her life serving.

In America, this cannot happen.

Not “unlikely.” Cannot. Structurally impossible.

Could a president try? Sure. Could Congress pass a law? Maybe. But it would face immediate constitutional challenge, separation of powers that actually separates, judicial review that can’t be ordinanced away, political consequences in the next election, media scrutiny that doesn’t require courage, and civil society that can mobilize without fear.

The Fifth Amendment says you can’t take property without due process and just compensation. When the Supreme Court allowed a controversial taking in Kelo v. City of New London (2005), there was national outrage. States passed new laws limiting eminent domain. The political backlash was severe.

And that was a case where SCOTUS allowed the taking.

Imagine if the government lost at the Supreme Court and then issued five executive orders saying “we’re taking it anyway.” The constitutional crisis would be immediate. The impeachment proceedings would begin. The system has antibodies.

India’s system has no antibodies.

Do I love the United States? Yeah. Damned straight. Wholeheartedly and without the tiniest reservation. Despite the people in charge today. Because loving a country isn’t about approving of its current leadership—it’s about trusting its institutional framework.

Property rights in America are imperfect. But they’re rights. Not privileges the government extends until it changes its mind.

This is why millions of us left. Not because we don’t love India—I’m writing this entire series, aren’t I? But because when you watch your mother win the highest legal victory possible and then see it erased by bureaucratic pen, you learn something fundamental about institutions.

You learn that rule of law isn’t about the laws written down. It’s about whether the government follows its own rules when following them is inconvenient.

You learn that judicial independence means nothing if judgments are suggestions the executive can override.

You learn that property ownership requires more than a deed—it requires a state that respects deeds even when keeping that property is profitable.

And you learn to be grateful—genuinely, profoundly grateful—for boring institutional protections that Americans take completely for granted.

The baseline matters. In America, you can’t lose in the Supreme Court and just issue ordinances until reality bends to your will. Judges have life tenure. States have genuine power. The federal government can’t simply decree new property rules retroactively.

That baseline? It’s everything.

So yes, critique America. I’m a free speech absolutist—have at it. I’ll join you. But recognize what we have: a system where the government plays by its own rules even when losing is expensive. Where Supreme Court decisions stick even when presidents hate them. Where property rights are protected not because the government is generous, but because it legally cannot do otherwise.

That protection is the entire reason millions of us can sleep at night.

This is why I live in Connecticut. India did fail me, just like it failed the Raja and just like it failed my mother. It fails everyone when a government refuses to uphold its own laws and its own judgments. Yes, I had every privilege—the best schools, the right connections, a mother who could argue before the Supreme Court. And none of it mattered. Not one bit. Because privilege is meaningless when the system is transparently corrupt. When even winning at the highest level means nothing, what good is advantage?

But it failed my mother most of all. She did everything right: studied law, practiced with integrity, took on a case no one else would touch, assembled a legal team through sheer force of reputation, won the highest judgment possible against the Indian government. And watched that government erase it because institutions bent to power instead of restraining it.

Now, over to Delhi’s landlord from hell, and how the same government that can ordinance away Supreme Court judgments treats ordinary citizens trying to convert a leasehold flat...

How We Got Here: The Colonial Gift That Keeps Taking

The Mahmudabad case isn’t an aberration. It’s the system working exactly as designed—a system the British created for extraction, not ownership, and independent India perfected.

In 1793, Lord Cornwallis introduced the Permanent Settlement, turning tax collectors (zamindars) into “proprietors.” But with a catch: they had to pay 89% of revenue to the British. The revenue was fixed so high that half the lands were sold between 1794 and 1807 for unpaid taxes. It wasn’t ownership—it was a revenue-extraction machine with a property deed attached.

The British innovation: Crown Land Doctrine. All land ultimately belonged to the Crown, even when “proprietors” were recognized. The state was the supreme owner. Everyone else was, at best, a tenant.

This principle survived Independence. It became the foundation for socialist state control. The modern leasehold system descended directly from this colonial framework: The state owns the land. You get to use it. For now.

The British created three contradictory property systems in different regions—Permanent Settlement, Ryotwari, Mahalwari—all focused on revenue extraction, all with unclear ownership. India inherited ALL of them simultaneously. The absurdity was baked in from the start.

Then Independent India doubled down.

Socialist India: Because Colonial Extraction Wasn’t Enough

In 1947, India inherited:

- 57% of land under zamindari.

- 7% of landowners owned 54% of the land.

- Land records “in extremely bad shape giving rise to mass litigation.”

The solution? Zamindari abolition in the 1950s. A noble goal. But it only removed the top layer while maintaining state supremacy. The government became the supreme landlord. Just with different bureaucrats collecting the rent.

(My father’s family lost their zamindari estates in this process. Watching property get confiscated runs in the family, apparently. We’re consistent, if nothing else.)

Oh, but the government was fair about it. They gave compensation. Rs 670 crores in cash and bonds—”Zamindari Abolition Compensation Bonds” carrying 2.5% annual interest. The bonds were supposed to be honored from the date of vesting until redemption.

Supposed to be.

Many zamindars reported the government simply stopped honoring the bonds. Payments ceased. The bonds became worthless paper. You know, like a check from someone who closed their bank account.

But wait, there’s more. The same playbook was used on the princes.

When 565 princely states voluntarily joined the Indian Union in 1947-1949, they were promised “privy purses”—guaranteed annual payments enshrined in the Constitution under Articles 291 and 362. In perpetuity. Constitutional guarantee. The deal that made Indian unification possible without bloodshed.

Then in 1970, Indira Gandhi decided these payments were “incompatible with an egalitarian social order.” The first attempt to abolish failed in the Rajya Sabha by one vote. So in true Indian fashion, the government tried again.

December 28, 1971: The 26th Constitutional Amendment abolished privy purses. Articles 291 and 362—deleted. Constitutional guarantees that facilitated the creation of modern India—erased. The princes who voluntarily gave up their kingdoms to join India were told: “Thanks for your sacrifice. About those guaranteed payments we promised? Never mind.”

See the pattern?

Make a promise. Get what you want. Break the promise. Claim it’s for socialism.

The zamindars got bonds that weren’t honored. The princes got constitutional guarantees that were deleted. And decades later, property owners get Supreme Court judgments that are ordinanced away.

It’s not a bug. It’s a feature. The feature is: promises from the Indian government have an expiration date determined by political convenience.

Then came the Urban Land Ceiling Act of 1976. The superb socialist vision: “Equitable distribution” through “socialisation of urban land.” The reality: It locked-up land from development, created bureaucratic nightmares, generated massive litigation, and forced benami transactions and black money. The World Bank’s 1987 verdict: it has “not lived up to expectations.”

Even after nationwide repeal in 1999, West Bengal kept it for years—a monument to ideology outlasting any connection to reality.

Academic research by Banerjee & Iyer (2005) found that areas with landlord-based colonial systems STILL have significantly lower agricultural investment, lower productivity, and lower health/education investment—DECADES after independence.

Colonial property institutions created locked-in disadvantages that socialist reforms couldn’t overcome because they preserved the fundamental problem: state supremacy over private property.

Lord Cornwallis designed a system for extraction. Mission accomplished. It’s still extracting—just now from Indians, and now with the enthusiastic participation of their own government.

The DDA: Delhi’s Development-Preventing Authority

If you want to understand why you can’t really “own” property in Delhi, meet the Delhi Development Authority. Created in 1957, the DDA acquired nearly 70,000 acres from surrounding villages and became the great socialist landlord of Delhi’s periphery.

Here’s the beautiful part: The DDA doesn’t sell you land. It leases it to you for 99 years. You can “own” a flat, but the land beneath it belongs to DDA. Forever.

The logic was noble (when seen through the lens of socialism): Prevent speculation, keep housing affordable, maintain state control. The result: A byzantine system where you pay crores for a house you don’t actually own.

The 99-Year Lease Trap

Let’s talk about that 99-year lease. Sounds reasonable, right? Your great-grandchildren’s problem.

Except the 99 years starts from completion of construction, not from when you take possession. So if there’s a five-year delay (and there’s always a delay), you actually get 94 years. Buy a flat that’s already 10 years old? You get 89 years. Buy one that’s 30 years old? You get 69 years, and banks start getting nervous about giving you a loan.

What happens at year 99? Theoretically, the land reverts to the government.

Will the government really evict millions of Delhi residents whose leases expire around 2047—India’s 100th Independence anniversary? Probably not. But the uncertainty means your property value starts declining after year 60, crashes after year 80, and becomes nearly worthless after year 90. Not to mention that a significant number of leases that were “acquired” from the British are now expiring and need to either be converted to freehold, or leased again.

Singapore solves this with clear policies: SERS (Selective En-bloc Redevelopment Scheme), VERS (Voluntary Early Redevelopment), government-funded upgrades. You know what happens at year 99.

In Delhi? You find out via ordinance.

The Conversion Nightmare

Starting in the 1990s, the government finally allowed converting leasehold to freehold. Pay a one-time fee, get a proper title, sleep easier.

Between 1993 and 2021, about 34,000 properties converted. Sounds good!

Then in late 2022, the Land & Development Office (L&DO)—which manages the colonial-era Nazul lands and refugee colonies—simply stopped processing conversions. No official announcement. Just an informal freeze.

By 2024, thousands of Delhiites were in limbo. They’d applied, paid fees, submitted documents. Nothing moved. The L&DO told the Delhi High Court it was working on a “new Standard Operating Procedure” and “revised conversion rates.”

For over two and a half years, nothing happened. Despite court orders. Despite “committed” deadlines.

It’s like the DDA looked at Kafka’s The Trial and thought “You know what? That’s a great instruction manual.”

The 15-Document Kafka List

When conversions were actually happening, here’s what you needed:

Demand-cum-allotment letter (notarized)

Seven passport photos (Why seven? Don’t ask questions. Asking questions is how you end up needing fourteen.)

NOC from the mortgage lender

NOC from the electricity company

NOC from the water company

A “sanctioned” building plan (or if missing: an affidavit + a new architect plan matching the old plan you don’t have)

All monthly installment receipts going back decades

Property tax receipts

Site photographs

For GPA holders: Multiple additional documents

For societies: Even more documents

The Catch-22: You need a building plan to convert. If the plan is missing, you need a new plan matching the old plan you don’t have. Any deviation triggers “composition” fees. But deviations are only discovered during the inspection triggered by your application.

So applying reveals violations that prevent the conversion you’re applying for.

It’s not a bug. It’s a feature. A feature designed by someone who read Kafka and thought “he’s not cynical enough.”

The Corruption Carnival

When official conversion is frozen for 2+ years, desperate landowners will pay anything for “alternative solutions.”

July 29, 2025: The CBI catches a DDA Dealing Assistant red-handed demanding Rs 50,000 to process a routine freehold conversion. He was caught accepting Rs 20,000 as first installment. This wasn’t expedited service. This was for NORMAL processing.

During the freeze, landowners reported being pressured to pay extra under the table for NOCs. Middlemen flourished. The process became so opaque that bribing your way seemed almost legitimate.

The conversion charges: Vary by authority and property type—fixed flat fees for DDA flats (a few thousand to a couple of lakhs based on zone and size, because nothing says “equitable” like arbitrary brackets), or around 6-10% of the land value for L&DO properties, plus a cheeky 33-1/3% surcharge if you’re a GPA holder. Stamp duty: 6% (males), 4% (females). Ground rent arrears with interest. Restoration charges. Composition fees for violations. For a Rs 1 crore property, you might cough up Rs 8-20 lakh total to convert—often gobbling up much of the 15-20% premium you’d gain from ditching leasehold for freehold, turning “ownership” into yet another bureaucratic punchline.

Milton Friedman understood: When you design a system where citizens must constantly seek permissions to secure their property rights, you create a bazaar of rent-seeking opportunities. Every approval point becomes a bribery opportunity. Where there’s a bureaucrat guarding a gateway, there’s someone willing to pay for a side door.

The socialist dream of “equitable distribution”? It worked. They distributed the graft to every approval point.

When Leases Expire: The Roshanara Cricket Club Requiem

September 2023. The DDA seals the Roshanara Cricket Club at 6am with a police escort.

The club was 101 years old. The “cradle of Indian cricket.” Where Lala Amarnath, Nawab Pataudi, and Bishan Singh Bedi (Americans: look them up!) learned to play. A piece of sporting history.

The leases had expired in 2012 and 2017. The club operated OVER A DECADE after the first expiry. The DDA accepted rent payments for years after expiry. No warnings. No transition plan.

Then, one day at 6am. Sealed. Re-entered. Game over.

The club asked for an extension. Other clubs older than Roshanara got extensions. But the DDA said no. The system is arbitrary by design.

The original lease: Rs 100-3,200 annual rent on 23.29 acres of prime Delhi land. The DDA claimed 3.5 acres were encroached (Rs 180 crore value).

The DDA now promises to “restore to past glory”—which in Indian government-speak means “sell for commercial development and pocket thousands of crores.”

It’s the same story everywhere: Leases that served “public purposes” (sports, community) suddenly become the “private property of certain individuals” when the lease expires. Then eviction. Then a commercial sale at market rates.

The hypocrisy is the point.

Eleven years to evict a cricket club after a lease expiry. Eight days to evict families from slums. India’s property law has a unique sense of urgency.

Eight Days to Destroy a Life: The Joga Bai Evictions

July 9, 2024: Eviction notices posted in the Joga Bai slums.

Deadline: July 17, 2024.

Eight days to uproot families who’d lived there for decades.

Affected: Daily wage laborers, rickshaw pullers, domestic helpers in Jamia Nagar—predominantly Muslim areas of Delhi.

No alternative housing. No rehabilitation. No support.

Abdul Rahman: “We have no other place to go. This is our home. We work hard every day, but if we lose our shelter, where will our families stay?”

Shabana Begum: “It feels like our future is being taken away.”

The statistics: 337,990 people at risk of homelessness in Delhi (2024). 278,796 people displaced by forced evictions in 2023. 49 evictions in 2023 = one every 7-8 days.

Delhi has the highest rate of forced evictions in India.

Eight days to evict families who’ve lived there 30 years. Eleven years to evict a cricket club after their lease expired. But 2.5+ years and counting to process routine freehold conversions? India’s property law has a unique sense of urgency: maximum speed for crushing the poor, maximum delay for helping the middle class, and maximum tolerance for the obscenely rich and well-connected. [Footnote: Large numbers of India’s “rich” got rich from connections, bribery and corruption, hence obscene. I’m a free market guy!]

The Builder Mafia: Who Profits from Chaos

The Mahmudabad case involved 1,100 properties worth over ₹1 trillion. The government can now sell them.

Who do you think benefits from that fire sale?

The Builder-Politician-Bureaucrat Nexus

In 2022, Aaditya Thackeray publicly defended the politician-builder nexus at a Real Estate Forum: “We both sell hopes and dreams.”

Finally, honesty. They’re both in the business of selling illusions and getting rich off desperation.

The money flow:

1. Politicians accumulate corrupt funds.

2. They route money to real estate.

3. Builders develop projects using political funds.

4. Money routed back during elections.

5. Bureaucrats provide illegal clearances.

6. Law enforcement protects the nexus.

Major builder families with political connections:

- Rajiv Singh (DLF): Rs 1,24,450 crore.

- Chandru Raheja (K Raheja Corp): Rs 42,585 crore

- Wave Group: Received 42% of commercial allotments in prime Noida sectors

The Scandal Hall of Fame

Adarsh Housing Society (2010):

- 31-story building meant for Kargil war widows.

- Politicians, bureaucrats, military officers grabbed flats at below-market rates.

- Of 103 members, only 37 from the army, only 3 associated with the Kargil war.

- CAG: The “Episode reveals how select officials could subvert rules to grab prime government land”.

- Current status: Supreme Court stayed demolition. The building stands.

Patra Chawl (2007-2022): Rs 1,034 Crore:

- 47 acres, 672 tenant families in Mumbai

- Contract: Build flats for tenants + 3,000 for MHADA.

- Reality: NOT A SINGLE FLAT built for tenants

- Land sold to 9 developers for Rs 901.79 crore.

- Sanjay Raut (Shiv Sena MP) arrested August 2022

- Tenants: Still waiting 15+ years later

Commonwealth Games (2010): Rs 70,000 Crore:

- Budget: Rs 1,620 crore → Rs 70,000 crore actual

- 400,000 people relocated

- ~70 workers died on sites

- Suresh Kalmadi arrested, spent 10 months in jail, claimed dementia during interrogation, then allowed to attend London Olympics

- That’s what India calls “accountability”

The pattern: Scandals get exposed, arrests happen, bail happens faster, convictions take decades if ever, buildings stay standing, money stays stolen.

It’s not corruption. It’s a business model.

Singapore: Proof It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way

Singapore has 99-year leaseholds too. The difference? They work.

How Singapore Does It

Housing & Development Board (HDB):

- 80% of 6 million residents live in HDB flats

- 89-90% homeownership (world’s highest)

- Over 1 million flats

What’s Different:.

- Lease terms are crystal clear.

- What happens at year 99 is defined: SERS, VERS, Lease Buyback Scheme.

- Every flat upgraded twice during lease (at 30 and 60-70 years).

- “No one will be left without a roof over their heads”.

- Policy changes are well-communicated, rules accessible.

- Financing rules account for lease decay.

- CPF (mandatory savings) makes housing affordable

Institutional Quality:

FactorSingaporeIndiaCorruption Index3rd globally (84/100)93rd (39/100)Processing TimeDays to weeksMonths to yearsPolicy ClarityCrystal clearOpaque, changingProperty RegistrationDays58 daysContract Enforcement505 days1,445 daysPrice-to-Income Ratio3.8 (affordable)11 (unaffordable)

Economic Outcomes:

- HDB prices rose 38% (2014-2024) despite 99-year lease.

- Market liquid, high transaction volume

- Banks readily finance with clear terms.

In India, leasehold properties depreciate as the lease shortens. After 60 years remaining, there’s a sharp decline. Below 20 years, close to worthless. And by then, banks refuse to finance.

It’s not the lease term. It’s the governance.

Singapore’s corruption index: 3rd globally. India’s: 93rd. The same 99-year lease concept, opposite execution. It turns out it’s not the lease term—it’s whether your bureaucrats view citizens as customers or marks.

The Economic Catastrophe: What India Is Losing

Hernando de Soto identified $9.3 trillion in “dead capital” in developing countries—wealth that can’t be leveraged because property rights are unclear.

India is his nightmare made real.

Dead Capital Everywhere

Trillions in real estate value just sits but you can’t use it as collateral because:

- Two-thirds of court cases are land disputes.

- Average resolution: 20 years.

- Ownership is “presumptive not conclusive”.

- Sale deeds record transactions, but don’t guarantee title

Every property in India is Schrödinger’s asset—simultaneously owned and not owned until you open the box and find a 37-year legal case inside.

Transaction Costs: Ronald Coase showed property rights assignments matter for efficiency when transaction costs exist.

India’s prohibitive costs:

- Multiple departments with conflicting records

- Manual records 140+ years old

- 64% mismatch between government records and actual holdings

- No integration of spatial and textual data

High transaction costs prevent Coasean bargaining that would lead to efficient resource allocation. The market can’t function when simply verifying who owns what takes decades and requires bribes at every step.

Housing Market Dysfunction

Supply Constraints:

- 36% decline in affordable housing supply (2022-2024)

- Housing shortage: 18.7 million urban units

- Yet: 11 million vacant homes.

- Developers focus on luxury (higher margins)

Affordability Crisis:

- EMI-to-income ratio: 61% (2024), up from 46% (2020)

- Price-to-income ratio: 11.

- Takes 11 years of total household income for a modest 90sqm apartment

- Property prices grew 9.3% annually vs. household income 5.4%

FSI/FAR Stranglehold:

- Mumbai: 1.33 recently increased to 3.0-5.0.

- Manhattan: 15

- Singapore: 8-25

- Tokyo: Unlimited since the 1960s

Low FSI creates artificial scarcity, raises prices, and forces sprawl. Bangalore loses Rs 20,000 crore annually to traffic congestion from sprawl caused by density restrictions.

Friedman understood: Quantity controls create shortages and deadweight losses, just like price controls.

India spends tens of billions on infrastructure. Then loses hundreds of billions because unclear property rights make infrastructure projects take twice as long. It’s like buying a Ferrari and filling it with diesel—you’re working really hard to sabotage yourself.

The Total Bill

Conservative Annual Deadweight Loss:

Housing shortage: 18.7 million units × Rs 30 lakh = Rs 56 lakh crore ($685 billion) in unbuilt value

Transaction costs: Legal disputes, title verification, bribes, litigation delays

Misallocation: Assets not going to the highest-value users

Innovation foregone: Property that could be business collateral sits idle

Total: $200-330 billion annually (5-9% of GDP)

Over a decade, fixing property rights could add $800 billion to $1.6 trillion to GDP.

Every year India delays, it loses hundreds of billions in potential output. The technology exists—GIS, blockchain, digital signatures. The economic analysis is clear.

What’s missing is the political will.

Because too many people benefit from the chaos.

The Counterfactual: What If We Had Real Property Rights?

Australia’s Torrens System (1858):

- State provides guaranteed titles.

- Central registry with unique property IDs.

- Single source of truth

- Result: Near-zero title disputes, transactions in days

If India had Singapore/Australia-level property rights security:

- Housing prices would likely be 30-40% lower (supply response)

- Credit markets would be something like 50% larger (collateral available)

- Infrastructure funding would double (the property tax base)

- GDP growth 1-2 percentage points higher

That’s not speculation. That’s what happens when you remove deadweight losses from unclear property rights.

We know the reform needed. We know the benefits. We know it’s technically achievable—India built theh UPI, implemented a GST, created the Aadhaar identity system.

But reform won’t happen. Because the system is working exactly as designed—just not for citizens.

Conclusion: The Reform That Won’t Happen

We know what needs to be done: - Conclusive titling system with state guarantee - Complete digitization of land records - Unified land authorities - Reduced FSI/FAR restrictions - Clear end-of-lease policies - Independent anti-corruption bodies with teeth

We know the cost of inaction: $200-330 billion annually.

We know it’s achievable. But vested interests benefit from dysfunction. The builder-politician-bureaucrat nexus profits from opacity. Every approval point is a bribery opportunity. The system is working exactly as designed—just not for citizens.

The Mahmudabad case isn’t ancient history. The Raja died in 2023. His properties are being sold now. Legal heirs deemed “enemies” despite being Indian citizens. A Supreme Court victory erased by five ordinances and a retroactive law.

A Cambridge-trained astrophysicist who returned to serve India, denied justice by a system that values power over law.

If they’ll do that to a Supreme Court judgment, imagine what happens to your conversion application.

Every year of delay costs hundreds of billions. Future generations will struggle to explain how a civilization that worshipped Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, made it nearly impossible to own property.

Then again, maybe they won’t struggle. Maybe they’ll just say: “It was India. The beautiful mess kept functioning despite itself.”

But here’s what I learned watching my mother’s victory get ordinanced away: The beautiful mess only keeps functioning for those who can afford lawyers, bribes, and backup plans.

For everyone else, it’s just a mess.

India liberalized toothpaste manufacturing in 1991 and created a consumer goods revolution. Thirty-four years later, we still can’t liberalize land ownership in our own capital city.

We freed Lakshmi to make products but kept her chained when it comes to property.

Somewhere, Lord Cornwallis is laughing. His extraction machine runs perfectly—just with different operators taking the cut.

And somewhere in Connecticut, I sleep soundly in a house I actually own, grateful every single day for boring institutional protections that Americans take completely for granted.

That’s not a criticism of India. That’s love from a distance. Love that recognizes when the gap between reverence and reality becomes too wide to bridge.

Until India builds institutions that protect property rights even when it’s inconvenient for the powerful, millions more will make the same choice I did.

Not because we don’t love India.

But because we learned the hard way: Property rights aren’t real unless the government can’t take them away on a whim.

And in India, five ordinances and a retroactive law proved they’re always just a whim away.

If you like my posts, you will like my book, The Science of Free Will. Among many other things, I talk about the future of AI and LLMs, whether bees have emotions, why traffic sucks, why Nobel Prize winning economists still don’t understand basic tax policy, and much more!

Previous posts: 1. The Paradox of India | 2. The Diaspora Paradox | 3. The Wedding Wars | 4. From Goddess Lakshmi to Ration Cards | 5. WhatsApp Uncles vs Wisdom Aunties | 6. From Lakshmi to Unicorns | 7. The Great Indian Cafeteria Wars | 8. The Mother Tongue Wars| 9. Gods In The Machine | 10. The Gender Paradox | 11. The Future of the Past | 12. Macaulay’s Children | 13.1. Language (Part 1) | 13.2. Language (Part 2)

Although my respect for India remains high—how all that order rises spontaneously out of chaos, so well explained in your earlier posts—with this latest post my elation for the country stemming from a recent visit, and my hopes for it going forward, have been tempered. The wind has been taken out of my sails given the lack of bedrock dedication to the rule of law and property rights. That the government has been captured by rent-seekers and corrupt players to the degree you outline suggests the full implementation of what some refer to as the American Idea, may be decades away.

What is the American Idea? Unlike most nations, America is less of a place on a map than it is a state of mind. The core of Americanism is summed up in the Declaration of Independence, which Thomas Jefferson once described as “an expression of the American mind.” That founding document stated many things, of which the recognition of the rights of individuals was sacrosanct. In doing so, America’s Founding Fathers consciously created a new polity—subordinating society and government to this fundamental law which heretofore had no foreign counterpart.

An incredible story with an expectedly sad ending. The Congress was not much better when it came to looking after the interest of the minority - read Muslim - community but the BJP is beyond the pale.