The Third Rail

How a "Temporary" 10-Year Policy Became an Immortal 75-Year Mathematical Impossibility Covering 60% of the Population

In 1930s Lahore—back when Lahore was still “India,” before partition tore the subcontinent apart—a young man stood beneath a window with a violin.

He wasn’t supposed to be there. The woman upstairs was a Kashmiri Brahmin. He was not. The scandal, had anyone discovered him, would have been considerable. Her family would have been outraged. His family would have been mortified. The neighbors would have talked for years.

He came back every evening anyway. Played until she agreed to marry him.

She did. They had my mother. And that, combined with some equally scandalous choices on my father’s side, is why I have absolutely no idea what caste I am.

This is not a figure of speech. I literally cannot be classified.

My mother’s side: half Kashmiri Brahmin (the grandmother who surrendered to the violin), half something-else-that-caused-the-scandal (the grandfather with the excellent taste in music and terrible judgment about social conventions).

My father’s side: Kayasthas from Uttar Pradesh.

And here’s where it gets interesting. Look up Kayasthas. I’ll wait.

The Wikipedia article reads like a theological dispute crossed with a family argument at Thanksgiving. Are Kayasthas Brahmins? Kshatriyas? Vaishyas? Shudras? The British colonial administrators couldn’t figure it out. Modern scholars can’t figure it out. The Kayasthas themselves have been arguing about it for centuries. Some claim descent from Chitragupta, the divine scribe of Yama, god of death—which would make us... what, exactly? Celestial stenographers? Cosmic bureaucrats keeping the afterlife’s paperwork in order?

My father’s family were also Zamindars—giant landholders under the British. Several villages in UP were their land before independence. All of that was taken afterward; the government gave them “Zamindari abolition bonds” as compensation, which they subsequently repudiated in entirely typical fashion. (If you want the full absurdity of how the Indian goverment “works”, I covered the “Mahmudabad” case in my post on property law. The pattern is: India promises compensation, India provides worthless judgment/paper, India shrugs.)

So let me create a model for my own caste identity:

I am 7.1 on the Brahmin Scale (which is logarithmic), but 9.7 on the Kshatriya Scale (which is linear), and potentially 2.5 on the Chitraguptavanshi Scale (which is modular). Depending on which colonial-era census you consult, which religious text you cite, and which relative you ask after their third whiskey, I am either a twice-born sacred thread wearer or basically a glorified clerk with landed pretensions.

My god. What an absolute load of old cobblers. In 2025! This is the garbage that people still believe?

To call this stuff nonsense is to be rude to nonsense. If I had to single out the ONE set of beliefs most damaging, absurd, idiotic, terrible, uncivilized, inhuman, ridiculous, and offensive to the dignity of each human being, then—after communism and socialism—caste is third.

Let me be clear about something the world is too polite to say.

Caste is a disgrace. A stain. A blot upon Indian civilization.

I know cultural relativism is generally correct. In the broad scheme of things, it’s a bit silly to claim one culture is massively superior to another. We should treat individuals as individuals, not as group statistics. I’ve said this throughout this series.

But sometimes this worldview encounters something it cannot fit into its box. Caste is one such thing.

Non-Indians are always, at least somewhat, afraid of being overly judgmental on this topic. Perhaps they fear backlash. Perhaps they fear they don’t quite understand the nuances. So let me do it for everyone, since I’m Indian and can say what outsiders won’t:

Caste is indefensible. Full stop.

You cannot defend pogroms. You cannot defend holocausts. You cannot defend slavery. You cannot defend racial discrimination. And you cannot defend a hereditary system that assigns human beings to categories of worth based on the accident of their birth, wrapped up in pious incantations about karma and dharma and “ancient wisdom.”

Mahatma Gandhi was once asked, “Mr. Gandhi, what do you think of Western civilization?” He replied: “I think it would be a wonderful idea.”

Ha. Very funny. Except the joke is upon him. No society that wants to call itself civilized should tolerate caste. India claims 5,000 years of continuous civilization. Five thousand years of this. That’s not a selling point. That’s an indictment.

Gregory Clark, in The Son Also Rises, documented that one of the longest periods of social dominance ever exerted by any community in human history was by the Brahmins of Bengal—who practiced ultra-strict endogamy to maintain their power across centuries. Congratulations. That’s the record we want to set. Longer than European aristocracies. Longer than Chinese mandarins. The gold medal in hereditary oppression (but not, I hasten to add, all that many at the Olympics).

The world allows India to get away with it because there’s too much money to be made by “getting along.” And “cultural sensitivity” prevents criticism. Business interests prevent pressure. Everyone wants to sell things to 1.4 billion people, so everyone looks away.

And this, by the way, is why the Hindu right screams constantly about “conversions”—about missionaries, about Muslims, about Christians supposedly stealing their flock. The people converting are overwhelmingly from lower castes. They’re leaving because Hinduism, as practiced, actively discriminates against them. Christianity offers equality. Islam offers equality. Buddhism—Ambedkar’s choice—offers equality. These religions say: you are not defined by your birth.

The upper-caste response isn’t “how can we make Hinduism more equal?” It’s “how can we stop these people from leaving?” What they’d really like is for the lower orders to stop being so uppity and accept their place in the cosmic hierarchy.

Well, they’re not accepting it. They’re converting. They’re emigrating. They’re inter-marrying. They’re finding escape routes. The hierarchy is dying from below, and the guardians of hierarchy are panicking. That’s what you’re watching when you see “anti-conversion” laws.

The very existence of caste consciousness is a fundamental denial of basic human rights. It is oppression dressed up as religion, discrimination wrapped in spirituality.

And THAT is why the reservation debate is so frustrating. Both sides accept the categories. The upper castes say “stop discriminating against us based on caste.” The lower castes say “discriminate in our favor based on caste.” Nobody says: “Stop. Treating. People. As. Castes.”

The argument is about how to distribute the spoils of a poisoned system, not about whether the poison should exist at all.

And THIS is the basis for reserving 60% of government jobs and university seats.

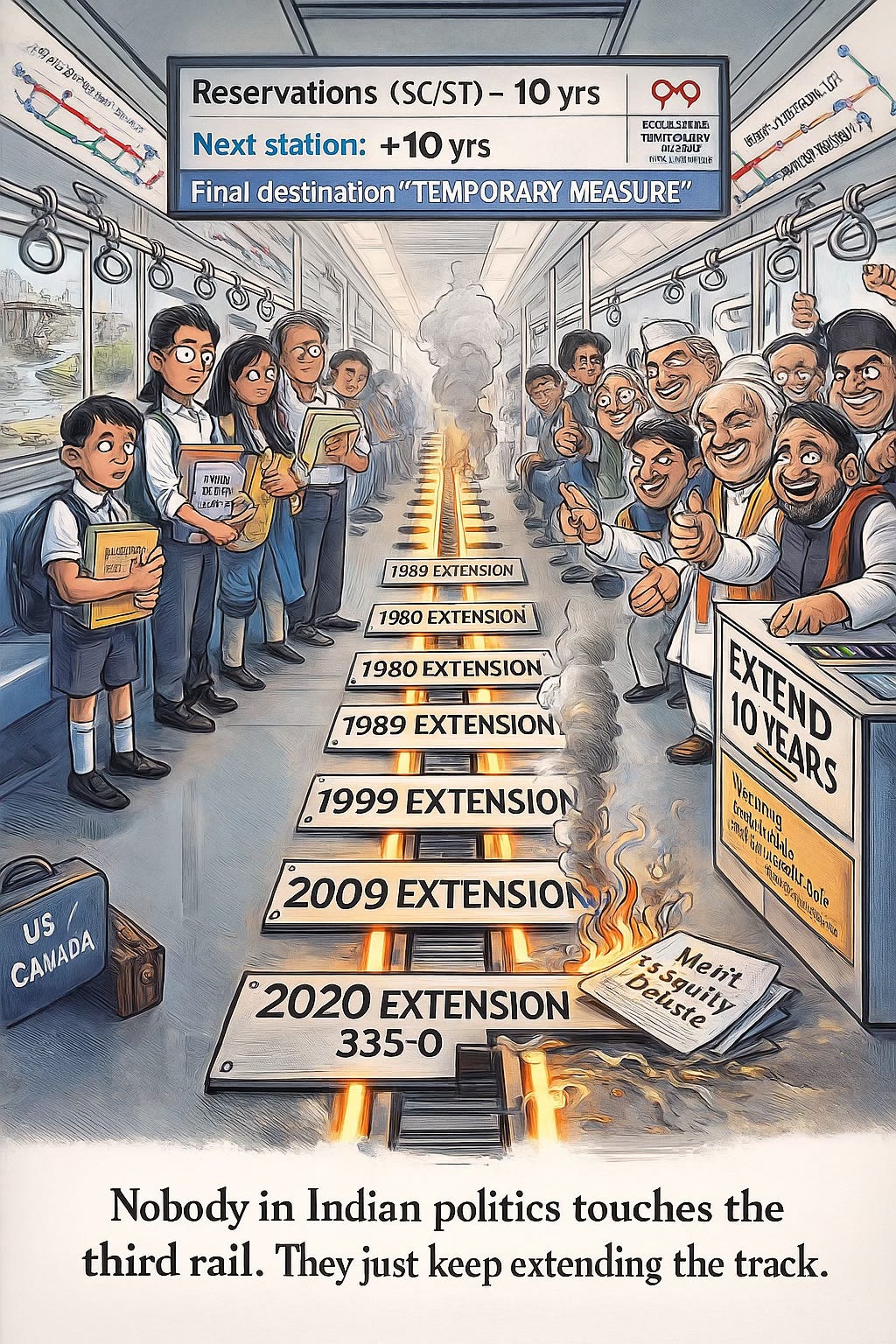

A system of classification so absurd that I literally cannot be classified—but which India has extended seven times, most recently by a vote of 335-0 in the Lok Sabha. Not a single legislator voted against.

In a parliament where members routinely attack each other with pepper spray and microphone stands, where debates about onion prices turn physical, where the BJP and Congress agree on essentially nothing—on this, absolute unanimity. The third rail of Indian politics doesn’t just electrocute you. It vaporizes you. Politicians don’t even mention it critically.

So let me mention it critically.

The Palace Fire That Wasn’t (And the Engineer’s Resignation)

Here’s something they don’t teach you in school: India’s reservation system didn’t begin with independence. It began in 1902, with fury.

Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj of the princely state of Kolhapur issued a proclamation reserving 50% of government jobs for backward classes. He was 28 years old. The order was explicit: “Of all the seats that go vacant from the date of this proclamation, 50% should be filled with the backward classes.”

The Brahmin establishment’s response was measured and thoughtful: they launched a vilification campaign through newspapers, organized social boycotts, and appealed to Lord Curzon, the British Viceroy, to overturn the policy. Professor Vijapure’s newspaper Samartha attacked both the Maharaja and his newly appointed non-Brahmin officials. Bal Gangadhar Tilak and the Poona orthodox circles rallied against Shahu. Brahmin leaders warned him to withdraw the changes “for the good of Hindu society.”

They lost.

Curzon ruled in Shahu’s favor. The British, practicing their usual divide-and-rule, rather enjoyed watching a loyal prince challenge Brahmin-led nationalist elites. The reservation policy stood.

(You may have heard the story that Brahmin priests set part of Shahu’s palace on fire in retaliation. It’s a good story. It appears in various retellings. There’s just one problem: no contemporary documentation supports it. The fire is likely a later embellishment—which tells you something about how charged this issue remains that people feel the need to invent arson to match the emotional temperature.)

Meanwhile, in Mysore, the Miller Committee of 1918 recommended gradual reservation—prompting Dewan M. Visvesvaraya to resign in protest, advocating meritocracy instead. This is the same Visvesvaraya later honored with the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian award. September 15th is celebrated as Engineers’ Day in his honor. India’s patron saint of engineering opposed reservations 107 years before the same debate rages in identical terms today.

The irony is so perfect it hurts: every year, on Engineers’ Day, we celebrate a man who resigned over the same policy argument we’re still having. We just conveniently forget why he resigned.

Then came the Poona Pact of 1932, which established the template for everything that followed. The British Communal Award had offered Dalits separate electorates—their own voting constituencies, their own representatives, political power independent of the Hindu majority.

B.R. Ambedkar, the Dalit leader who would later draft India’s Constitution, initially welcomed this. Separate electorates meant Dalits could choose their own leaders without Hindu approval. It was genuine political empowerment.

Gandhi launched a fast-unto-death in protest.

Let that sink in. Gandhi—the Mahatma, the apostle of non-violence, the moral conscience of the independence movement—threatened to kill himself unless Dalits gave up their independent political power.

Ambedkar, under immense pressure to save Gandhi’s life (and facing the prospect of being blamed for his death), signed an agreement abandoning separate electorates for reserved seats within joint electorates instead. He later called it “blackmail.”

The Constitution’s architects then inserted Article 334, providing that political reservation would cease after ten years—January 26, 1960. Ambedkar reportedly said reservation “beyond 40 years should have been barred by any means.”

That was 65 years ago.

Since then, Article 334 has been extended seven times through constitutional amendments—in 1959, 1969, 1980, 1989, 1999, 2009, and 2020. Not a single extension has faced meaningful opposition. The most recent passed 335-0.

The only reservation ever actually removed? Two nominated seats for Anglo-Indians—a community with no electoral power. Everyone else’s quotas are immortal.

What started as 22.5% for SC/ST expanded to include 27% for OBCs in 1990, and 10% for “Economically Weaker Sections” in 2019, pushing total central reservation to 59.5%. Tamil Nadu maintains 69% by placing its quota law in the Ninth Schedule, rendering it immune from judicial review. The Supreme Court’s “inviolable” 50% ceiling from Indra Sawhney (1992)? Violated routinely. Tamil Nadu ignores it. The EWS quota ignores it. Courts redraw the voltage zones because they can’t actually enforce their own rulings.

The “temporary” measure designed to last 10 years is now 75 years old, covers the majority of the population, and shows no signs of ever ending.

The Mathematics of Impossibility

Let me walk you through the numbers, because the numbers are where absurdity becomes arithmetic.

Central government quotas:

- 15% for Scheduled Castes

- 7.5% for Scheduled Tribes

- 27% for Other Backward Classes

- 10% for Economically Weaker Sections

- Total: 59.5% before horizontal reservations

State variations:.

- Tamil Nadu: 69%

- Maharashtra: attempted 62% (struck down, revived, challenged)

- Bihar: attempted 65% (struck down by Patna High Court, June 2024)

- Several northeastern states: up to 80% for tribal populations

Now let’s do the IIT math, because nothing illustrates the squeeze like India’s premier engineering institutions.

Across 23 IITs offering approximately 23,000 B.Tech seats annually, here’s the breakdown after accounting for all quotas plus 5% horizontal reservation for persons with disabilities plus 20% supernumerary seats for women:

Only about 14.5% of seats remain unreserved for general category males.

If you’re an upper-caste Hindu male from a family that earns too much to qualify for EWS, your son is competing for roughly one in seven seats at India’s premier engineering institutions. The other six are spoken for before anyone takes an exam.

The competition ratios are staggering. SSC CGL 2023: 13 lakh applicants for 8,913 posts—a 1:146 ratio. The recent railway recruitment drive: 30 million people for 90,000 positions. Junior ticket collector positions specifically: odds of 1,800 to one.

But here’s the absurdity within the absurdity: while millions cram for these exams, 42,000+ reserved positions in central government remained unfilled as of 2020—including 5,559 SC positions, 5,463 ST positions, and 6,747 OBC positions in Railways alone.

The system reserves jobs that don’t get filled while millions prepare for exams for seats that don’t exist. It’s like a restaurant that won’t seat anyone at half its tables, then complains about the line outside.

The Creamy Layer Comedy

To prevent the relatively well-off among backward classes from monopolizing benefits meant for the truly disadvantaged, the Supreme Court created the “creamy layer” concept. OBC candidates whose families earn above ₹8 lakh annually are excluded from reservation.

Sounds reasonable, right? Watch how India implements reasonable ideas:

Agricultural income doesn’t count toward the threshold. Own ten thousand acres of farmland? Still OBC if that’s your income source. Government salary from Group C or below doesn’t count. So an OBC government employee’s children can still access OBC quotas.

But here’s the real kicker: For SC/ST, there is no creamy layer exclusion at all.

This means third-generation IAS families—whose grandparents entered government service through the SC quota, whose parents rose through SC quota promotions, who themselves attended elite schools and speak better English than their “general category” classmates—continue accessing the same quotas designed for manual scavengers.

In August 2024, Justice B.R. Gavai (himself SC) suggested that creamy layer should apply to SC/ST as well. The recommendation ignited controversy precisely because it’s so obviously reasonable yet so obviously politically impossible.

Justice Gavai noted that only 1.13% of SC families have a member in Group A services—the cream is so thin “you need a microscope to see it.” Yet proposing to exclude even this microscopic cream triggers outrage. Reasonable ideas in India are like reasonable ideas in a madhouse: everyone agrees they’re reasonable, then throws furniture at anyone who tries to implement them.

The Rohini Commission found that 97% of OBC reservation benefits went to just 25% of OBC sub-castes. Nearly 1,000 OBC communities received nothing at all. The benefits designed to uplift the backward are captured by the relatively forward among the backward.

And within SC categories? In Andhra Pradesh, 59 castes compete for the 15% SC quota. Madigas (48.29% of SC population) argue that Malas have monopolized the benefits. The data supports them: 76.2% of state IAS officers are Mala versus 23.8% Madiga.

The Mala response, reportedly: “The Madigas eat beef, drink and loaf around, whereas we work hard.”

Dalits practicing untouchability against other Dalits. The oppressed ranking their oppression. The August 2024 Supreme Court ruling allowing sub-classification within SC opened a new front: now we can subdivide the subdivisions. Where does it end? Coming soon: Group 1A (”most most backward”) getting 0.5%, Group 1B (”most most backward but very slightly less so”) getting 0.5%. It’s turtles all the way down.

When I First Heard This Nonsense

I was about thirteen or fourteen when I first heard of “reservations.”

By then, I’d already been reading Friedman, Russell, Hume, Smith, and Hayek. Not because anyone assigned them—because I was curious, and because India’s socialist absurdity had made me hungry for explanations of why everything and everyone seemed so universally stupid. These thinkers had answers. They made sense. They treated human beings as individuals with rights, responsibilities, and dignity.

So when someone explained reservations to me, my reaction was: Say what? Say that again?

Because you are deemed to be of “caste X” you get preferences that other people don’t? What happened to individual rights? What happened to individual responsibilities? What happened to equal treatment under the law? What happened to treating people as responsible adults with their own abilities, inclinations, and potential?

I went home and thought about it. I waited to hear my family discuss it. Surely they would explain. Surely there was something I was missing.

Nothing. Not a single member of my family, ever, to the best of my recollection, mentioned caste in any context. Not even my mother—she who laid down the law with the force of a thousand neutron bombs, who had opinions about everything from my grades to my haircut to my posture to my friends to my future—ever used caste as an argument for anything, ever, at least not within my hearing.

This was a woman who could deploy guilt like artillery and disappointment like chemical weapons. If caste had mattered to her, I would have heard about it. I heard about everything else. I heard about everything else multiple times, with footnotes and cross-references and historical context and implications for my immortal soul.

Caste? Silence.

Which told me something important: even in a country obsessed with this nonsense, you could simply... not participate. You could refuse to acknowledge the categories. You could treat people as individuals. You could, in effect, opt out.

This more or less hardened my attitude toward morons, moronic attitudes, and the Indian government (which is, let’s be honest, largely a collection of morons). To this day, if someone says something moronic, I will either call them out on it (if I have the energy, which is rare) or stay silent and later think: Fuck ‘em.

In India, I learned one enormous skill: the ability to stay entirely sphinx-like, saying nothing at all, for hours on end. Given the amount of nonsense bandied about when I lived there—and seemingly still is—this is a survival skill. And, nowadays, with certain groups in America, it’s coming in extremely handy.

Why “Merit” Is a Fighting Word (And Why I Don’t Care)

The upper-caste argument: “We worked hard. We studied. We earned our place through competitive exams. Now you’re giving seats to candidates with lower scores based on accidents of birth. This kills merit. This destroys excellence. This is unfair.”

The lower-caste counter-argument: “Merit in India means the result of upper-caste privilege—access to better schools, private tuitions, English at home, freedom from financial stress, family networks, role models. What you call merit is historical advantage converted into modern credentials.”

Both arguments contain truth. I don’t care about either.

Here’s what I care about: treating people as individuals.

Not as representatives of categories. Not as inheritors of ancestral guilt or ancestral grievance. Not as statistics in someone’s social engineering project. As individuals. Each person with their own abilities, their own limitations, their own choices, their own responsibilities.

The entire reservation debate is conducted on terms I reject. “How much should we discriminate by caste?” is the wrong question. The right question is: “Why are we discriminating by caste at all?”

Yes, caste discrimination existed and exists. Yes, it’s evil. Yes, something should be done. But the solution to discrimination based on group identity is not more discrimination based on group identity. The solution is to stop—to actually stop—treating people as members of groups rather than as individuals.

US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts said it plainly: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

The same applies to caste. Obviously.

But try saying that in India. Watch what happens. Watch the instant accusations: elitist, privileged, out of touch, doesn’t understand ground realities, hasn’t suffered, how dare you. The debate is rigged. Anyone who questions the framework is accused of defending the status quo. Anyone who suggests treating people as individuals is told they’re ignoring history.

I’m not ignoring history. I’m refusing to be imprisoned by it.

Here’s what exposes the whole debate as theater: the management quota.

Private engineering and medical colleges routinely reserve 15-20% of seats as a “management quota”—filled via hefty donations. A seat that costs ₹2 lakh through competitive examination costs ₹50 lakh through the management quota. Rich kids with lower scores than reserved-category students buy their way in.

Where are the protests? Where are the tweets about merit? Where are the op-eds about excellence being destroyed?

Silence.

India runs a twin quota system: one based on caste to uplift the historically oppressed, one based on money to uplift the already privileged. The former gets debated endlessly. The latter is an open secret mentioned by nobody.

The media that screams about merit? Oxfam found that 106 of 121 newsroom leadership positions are occupied by upper castes. Three of four TV anchors are upper-caste. Zero Dalit or Adivasi anchors among 87 analyzed.

Cricket commentator Harsha Bhogle tweeted: “Thankfully in sport you cannot agitate for the right to run 50m in a 100m race.”

The tweet went viral. Nobody noted that the sports establishment—coaches, selectors, administrators, media—that identifies “talent” operates through the same caste-mediated networks as everything else. The 100-meter race Bhogle imagines as fair requires first being noticed, then selected, then coached, then promoted. Each stage filtered through social networks where surname and background matter.

But sure. Merit.

The Suicides That Changed Nothing

I need to tell you about 1990, because it reveals how charged this issue became.

When Prime Minister V.P. Singh announced implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendation—27% OBC quota in central government jobs, pushing total reservation to 49.5%—upper-caste India erupted.

Students poured into the streets. They boycotted classes. They clashed with police. And some of them set themselves on fire.

On September 19, 1990, Rajiv Goswami, a 19-year-old Delhi University student, doused himself in kerosene and struck a match. The image of him engulfed in flames screamed from newspaper front pages.

He survived, barely. But his act inspired a wave of copycat self-immolations. In total, 159 people attempted suicide over OBC reservations. 63 died.

Monica Chadha, a young woman who immolated herself, remained defiant on her deathbed: “I want to teach a lesson to V.P. Singh. I am proud of what I have done.”

Another protester’s suicide note bequeathed her eyes to the Prime Minister so that “he could see the misery” of upper-caste students.

V.P. Singh’s government fell within months. But the policy survived. The Supreme Court upheld it in 1992. The quotas remain. The students who burned themselves accomplished nothing except dying.

I understand their anguish. The sense that rules were changing mid-game. The feeling of futures being redistributed by bureaucratic fiat.

But here’s what I thought at the time, and still think: If you don’t like the rules of the game, you don’t have to play the bloody game.

Too many people assume the rules are fixed, that you must play within them, that the only question is how to win under existing conditions. No. You can choose not to play. You can find another game. If India’s game is rigged—go find one that isn’t.

Exit is the loudest voice.

Even before all this, I was planning my departure. Not because of reservations specifically—the whole system was suffocating—but with the same underlying logic: this place is insane, these rules are moronic, the people in charge have the IQ of a dead donkey--I refuse to participate.

By 1984, I was gone. Columbia. Electrical Engineering (and then Physics at UT). A country where nobody asked about my caste because nobody knew what caste was.

The students who stayed and burned? They’re still debating the same quotas, 35 years later. Extended seven times. 335-0.

Fuck ‘em remains the correct response to morons and moronic systems. The best revenge is escape.

Same Planet, Different Universes

In June 2023, the United States Supreme Court struck down race-conscious college admissions. After 45 years, the Court ruled such programs lacked “meaningful end points.”

A few months later, India’s Parliament voted 335-0 to extend caste-based reservations for another decade.

The contrasts are stark:

US affirmative action in higher education lasted 45 years before being struck down; India’s system has run 75 with no endpoint in sight. US affirmative action never permitted formal quotas—only considering race as a “plus factor”; India mandates specific percentages. US affirmative action in employment exists but remains limited and contested; India reserves specific percentages of government jobs and promotions by constitutional mandate. The US created majority-minority electoral districts through the Voting Rights Act; India reserves actual legislative seats for SC/ST communities. US affirmative action helped minorities (13% Black, 19% Hispanic); India’s reservations cover 59.5% of the population—affirmative action for the majority.

But here’s the deepest difference: race in America is largely visible. Caste in India is invisible.

You cannot tell by looking at someone whether they’re Brahmin or Dalit. You have to deduce it from their name, occupation, family history, manner of speech, where they live. The very act of caste discrimination requires investigation. You have to learn the codes. You have to actively practice social detective work.

This invisibility makes the system simultaneously more pernicious AND more absurd.

More pernicious because discrimination requires intention and effort—it’s not automatic prejudice but cultivated prejudice.

More absurd because the categories are already dissolving. Inter-caste marriage rates are increasing rapidly in urban areas. My grandfather’s violin worked in 1930s Lahore—and it’s working across India today. Young urban Indians often don’t know their sub-caste and don’t care. The distinctions are becoming meaningless even as the government insists they be checked on every form for admission, selection or employment.

So what happens when you have caste-based reservations for people with mixed backgrounds? What would my children--one-eighth Kashmiri Brahmin, quarter mystery-Kayastha, quarter Italian, quarter Austro-Hungarian, and native-born Americans-—pick on a form if they ever applied for anything in India? (This is a thought experiment—a physicist would say a Gedankenexperiment, à la Einstein—I hasten to add.)

The system doesn’t get fairer. It gets more absurd. You’re requiring people to identify with categories they’re actively trying to erase through the most fundamental human act: falling in love with the “wrong” person and marrying them anyway.

The Violin Versus the Vote

The caste system is dying from the bottom up.

Love. Urbanization. Economic mobility. Sheer boredom with ancestral grievances. Young people who don’t know what gotra means and don’t care to learn. Mixed marriages that would have caused riots two generations ago, now causing merely raised eyebrows and whispered gossip.

My grandfather knew this when he picked up his violin in 1930s Lahore. He was voting against the system one serenade at a time.

The reservation system keeps caste alive from the top down.

Constitutional amendments. Vote-bank politics. 335-0 parliamentary votes. Caste certificates required for every reservation application. A forthcoming caste census—the first since 1931—because the government wants even more granular data on categories it claims to be eliminating. The government insisting you identify as something your grandchildren won’t remember or understand.

The violin is winning. Slowly. But the government keeps extending the intermission.

The “temporary” 10-year measure will be extended in 2030, 2040, 2050. It will still be “temporary” in 2100. Politicians will still vote unanimously to continue it. The third rail will still be electrified.

But somewhere, a young man with a violin—or a guitar, or a Spotify playlist—is standing beneath a window, playing for someone his family thinks is wrong. And she’s going to say yes. And their children won’t know what caste they are.

That’s the only reform that actually works: millions of individual humans making individual choices, ignoring the categories, refusing to play the game.

The government can extend reservations forever. It can’t stop the violin.

Next: How the IT sector quietly bypassed the entire system, why dominant castes are rioting to be declared “backward,” and the ultimate escape valve—leaving.

If you enjoyed this, you might enjoy my book, “The Science of Free Will”. Among many other things, I explore why we can’t trade with ants, what that has to do with the future of AI, and why we need a Supreme Court if the world is deterministic.

The India Paradox is a series exploring how the world’s most diverse democracy somehow functions despite—or perhaps because of—its beautiful contradictions. Previous posts available at samirvarma.substack.com.

Yeah but Indians don't think of themselves as individuals, or at least that's not their primary identity. Most Indians' primary identity is their caste (or "community", not entirely sure what the difference is) or their religious sub-group coupled with their linguistic identity. Next would probably come family (?) and then maybe their profession?

I also thought that treating people like individuals was wonderful when I lived in America, and I still do in the sense that I see the advantages to that worldview. But the thing with human behavior is that believing something - or even knowing it to be true - doesn't have much of an effect. (e.g. I'm an atheist but no social or even legal system cares do they now)

I did enjoy the first half of your essay though

“Exit is the loudest voice.” That’s a great reminder. Thanks for a great article.