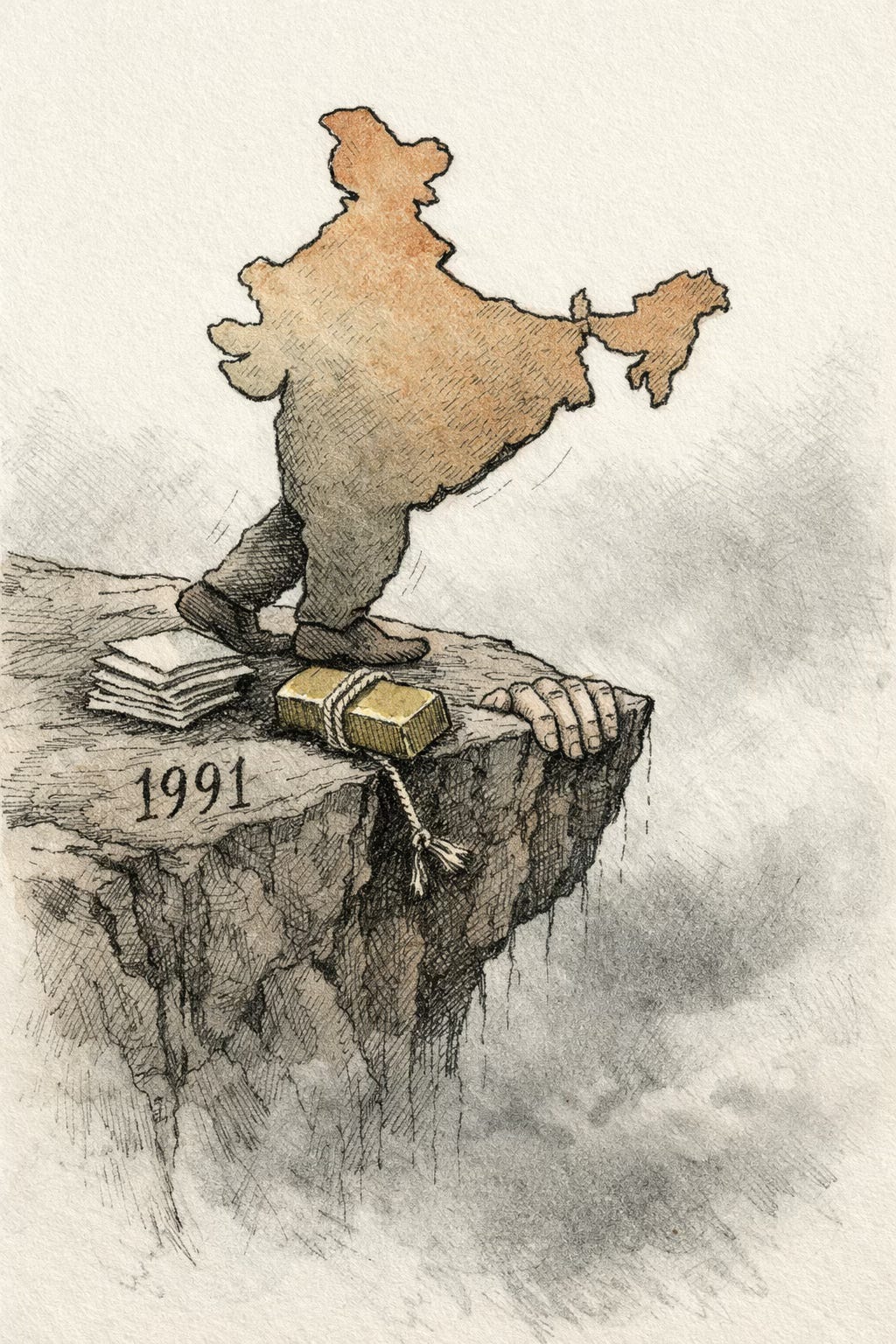

The Precipice

How a Partition Refugee, a Polyglot Novelist, and a World Bank Economist Found Themselves Standing Between India and Civilizational Collapse

In 1991, I was at the University of Texas at Austin, getting my PhD in physics. Head down, working very hard, no time to think about India at all.

This was deliberate.

India was not something you thought about if you could help it. It was cringe-inducing to be identified as “Indian” abroad. When people asked where you were from, you’d say it quickly and change the subject. Or you’d emphasize that you’d left, as if to say: I escaped.

Why? Because India meant one of two things in the American imagination: starving people, or some large-scale calamity. Whenever there was a famine or flood, that’s when India made news. Riots. Assassinations. Disasters. That was it. Those were the only stories.

India was a “shithole country”—except it was MUCH worse than a shithole. It was that special category of failure: big enough that everyone knew about it, poor enough that everyone pitied it, and dysfunctional enough that no one expected anything from it. The Hindu rate of growth had guaranteed that while the rest of Asia was sprinting ahead, India was walking backward on a treadmill. Taiwan was building semiconductors. South Korea was launching Hyundai. India was still debating whether to allow a second brand of cola.

My classmates at UT would sometimes ask about India—curious, well-meaning questions. “What’s it like there?” I learned to give vague answers. How do you explain a country where you need a permit to buy an airline ticket? Where producing too many cars is a crime? Where the government controls how much steel you can use to build your house?

You don’t. You change the subject. You talk about physics instead.

So I didn’t follow the news from home. What was there to follow?

A few years later, my mother sent me one of her characteristically silly letters with some line about “when will you come to India to contribute to nation building?” In Hindi, we’d say kehne ki baat hai—said because it sounds good to say, not because she meant it. Said for effect, not reality.

I didn’t respond. By then, I’d learned that things had certainly bottomed. But I didn’t know that something remarkable had happened in 1991. That three men I’d never heard of had prevented a catastrophe I’d never imagined.

This post is about those three men.

The Night India Hit Bottom

May 1991. Mumbai. Night.

While politicians slept, trucks were loading gold—67 tonnes of it—at the Reserve Bank of India’s vaults in South Bombay. Essentially all of India’s gold reserves. The trucks drove 35 kilometers to the airport under armed guard. There, the gold was loaded onto chartered cargo planes.

Commercial airlines had refused the job. Too risky. Too desperate.

Between May 21 and 31, four flights carried India’s treasure out of the country: 20 tonnes to UBS in Switzerland, 47 tonnes to the Bank of England in London. The RBI had to charter something called “Heavy Lift Cargo Airlines” because nobody else would touch this operation.

The gold was collateral. India was pawning its jewelry.

If you want to understand what this meant culturally, consider: In India, gold isn’t just an asset. It’s sacred. The goddess Lakshmi is depicted sitting on gold coins. Indian weddings feature kilograms of gold because “Does she have gold?” is the first question asked about brides. Women remove their gold only at death or divorce.

And here was the nation shipping its treasure to its former colonizer. At night. In secret. Like a family selling heirlooms to pay the landlord.

When the news leaked, there was public outrage: “We have pawned our mother’s jewelry!”

The operation raised $600 million.

It bought India about three weeks.

Foreign exchange reserves had fallen to $1.2 billion—enough for roughly fifteen days of imports. Fifteen days until the food shipments stopped. Fifteen days until the oil stopped. Fifteen days until a nuclear-armed nation of 900 million people defaulted on its debts.

What happens when a country that size defaults? What happens when the imports stop?

We know what happened to the Soviet Union. It collapsed. India was heading there—fast.

The Most Important People You’ve Never Heard Of

Three men you’ve probably never heard of—P.V. Narasimha Rao, Manmohan Singh, Montek Singh Ahluwalia—may be the three most important people of the late 20th century.

Bold claim. Audacious, even. Let me defend it.

Here are the numbers. In 1991, over 45% of Indians lived below the poverty line—roughly 400 million people. By 2024, extreme poverty in India had fallen to under 3%.

That’s 400 to 500 million people lifted out of poverty.

The largest democratic poverty alleviation in human history.

For comparison, consider what else the 20th century offered:

The Marshall Plan? That rebuilt already-developed European economies devastated by war. Impressive, but that’s reconstruction, not construction. Europe knew how to be rich; it just needed to recover.

China’s reforms under Deng Xiaoping? Comparable scale, yes. But achieved through authoritarianism—Tiananmen Square, the one-child policy, the suppression of Uyghurs. The human rights costs were staggering.

The Green Revolution? Prevented famine, absolutely. But it didn’t create sustained growth. It kept people from dying; it didn’t lift them into the middle class.

The combined efforts of the UN, World Bank, and IMF over 75 years? Arguably less total impact than what these three men set in motion.

Nothing else comes close to democratic poverty alleviation at this scale.

And here’s the thing about crises: they don’t automatically produce reform. Crisis alone doesn’t fix anything.

Argentina has had crisis after crisis—and keeps defaulting, keeps returning to the same failed policies. Greece in 2010 accepted bailouts, changed almost nothing structural, and remains economically fragile. Venezuela’s oil crises led not to reform but to doubling down on socialism, and now people eat from garbage trucks.

The Soviet Union faced a crisis and collapsed. It didn’t reform. It disintegrated.

India could have gone any of those directions. What makes these three men remarkable isn’t that they faced a crisis—it’s that they converted crisis into transformation. That almost never happens.

And because it worked—because the catastrophe was prevented—nobody remembers.

You can’t feel gratitude for the plane that didn’t crash. You can’t celebrate the engineer who prevented the disaster you never experienced. The counterfactual isn’t real to anyone.

This is why India forgot them. But that’s for Part 3. First, let’s understand what they were saving us from.

The Architects of Disaster

Before we meet the heroes, we need to understand the system they inherited—and the people who built it.

Here’s something nobody tells you: many of India’s socialist controls didn’t originate with Nehru or with Marx. They came from the Defense of India Rules of 1939—wartime emergency measures the British enacted when World War II broke out.

Think about that. The British needed to control a vast subcontinent with a tiny number of administrators. As one economist put it, “It is a miracle that such a small number of Britishers controlled this large territory.” The entire colonial civil service was built around control—not development, not prosperity, but control. That was literally the job description.

After independence, we didn’t dismantle this colonial apparatus. We expanded it.

Between 1948 and 1952, independent India passed the Imports and Exports Control Act, the Industrial Development and Regulation Act, the Control of Capital Issues, and more. We took the Raj’s emergency wartime measures and made them permanent peacetime policy.

The irony is too perfect: we fought colonialism, won our freedom, kept the colonizer’s control mechanisms, and applied them to ourselves with even greater enthusiasm than the British had.

The British controlled India because they wanted to extract wealth. We controlled India because we thought control was the same as development.

The Statistician Who Strangled Growth

P.C. Mahalanobis (1893-1972) was genuinely brilliant. The Mahalanobis distance—a statistical measure he invented—is still used in cluster analysis worldwide. He founded the Indian Statistical Institute, which remains a world-class institution. All legitimate achievements.

Then Nehru, his friend, put him in charge of economic planning. This was like asking a chess grandmaster to run a hospital because he was good at thinking ahead.

Mahalanobis designed the Second Five Year Plan (1956-61), which became the template for India’s economic disaster. His “Mahalanobis model” was an Indianized version of the Soviet approach: emphasize heavy industry, state control, import substitution. Central planning by expert statisticians who would calculate exactly what the economy needed.

In other words, exactly what Friedrich Hayek had warned against in The Road to Serfdom: the fatal conceit that brilliant people could plan an economy better than markets could coordinate it.

The model “provided the statistical foundations for state-directed investments and created the intellectual underpinnings of the License Raj.”

The same mathematical mind that created an elegant statistical measure created an elegant economic catastrophe. Mahalanobis was a genius. His planning model strangled Indian enterprise for forty years. Both statements are true. Welcome to the India Paradox.

The Communist Who Infiltrated Congress

Mohan Kumaramangalam (1916-1973) had quite the resume: Eton-educated, Cambridge Union president, Communist Party of India member.

Then he joined the Congress Party.

If that sounds like a contradiction, it wasn’t—it was strategy. The “Kumaramangalam thesis” was explicit: communists should infiltrate Congress from within, pushing it leftward. It worked brilliantly. An old Etonian communist became a minister in Indira Gandhi’s government and drove the nationalization wave of the early 1970s—coal, steel, copper, insurance. One industry after another brought under government control.

His first act as Minister of Steel and Mines: nationalize the mining industry. Because of course.

He died in a plane crash in 1973, before he could see the full consequences of his policies. Some people have all the luck—they get to start fires and leave before the building burns down.

Why Nobody Noticed the System Was Failing

Here’s the puzzle: India’s intellectuals visited the Soviet Union constantly throughout this period. They went on press junkets, government trips, academic exchanges. They came back impressed. They wrote glowing reports.

Nobody mentioned the shortages.

Years later, one economist finally put it together. He remembered that his friends in Moscow would ask visitors to bring soap and toothpaste. “Really simple things. You can’t understand why they don’t have access to that.”

But he didn’t connect the dots at the time. “In hindsight we completely understand the shortages were pervasive, even for the elites. We didn’t put it together because everything looked so good.”

Only after 1991, when he drove through East Germany, did he see the trick: “You go through a city and the main road looked very nice. You just went one block in—it was falling apart.”

The Soviets had Potemkin-villaged their own cities. And India’s intellectuals had been fooled by careful staging for forty years.

They couldn’t see the failure because they were never shown it. And because they couldn’t see it, they kept recommending the same failed model.

The Labyrinth

Let me describe what it actually took to start a business in pre-1991 India. This comes from Rakesh Mohan, who later helped dismantle the system—after first having to map its full horror.

To start ANY industry, you needed:

Industrial license from the Ministry of Industry (determining what you could make, how much, and where)

DGTD clearance—the Directorate General of Technical Development had to approve your technology

Import licenses for machinery (capital goods)

Import licenses for raw materials (intermediate goods)

A commitment to show how your imports would decrease over the next 5-7 years

Foreign Collaboration clearance for any foreign technology

Control of Capital Issues clearance from the Ministry of Finance if you wanted to raise money from the public

MRTP clearance from the Ministry of Company Affairs if your company was above a certain size

And THEN—only then—could you go to the Reserve Bank of India and apply for foreign exchange.

Each of these approvals could take months. Years. Each had its own forms, its own procedures, its own officials who needed to be satisfied. Each was an opportunity for delay, for obstruction, for the peculiar Indian art of the bribe disguised as “facilitation.”

And if anything changed—if you wanted to add a product line, expand capacity, use a different raw material—you started over. New applications. New committees. New delays.

“In a sense,” Mohan observed, “it is a miracle that we had as much industrial growth as we did.”

It gets better. There was a cement controller. A coal controller. A steel controller. To build a house, you needed a cement permit to get access to cement. Then a steel permit to get steel. This didn’t get decontrolled until 1981-82.

The Bureau of Industrial Costs and Prices controlled cement prices, steel prices, almost all drug prices, sugar prices—”most things, actually.”

The Permit Was Harder Than the Cash

Here’s a story that captures the era perfectly.

To buy an airline ticket for international travel, you needed something called a P-form—a permit for the corresponding foreign exchange.

In 1964, when Rakesh Mohan (then a schoolboy) was going to England on a scholarship, his father went through the bureaucratic nightmare of getting the P-form approved. Finally, success! They rushed to the Air India travel agent, papers in hand, ready to book the ticket.

His father realized he had forgotten to bring actual money.

Fortunately, his uncle happened to have cash with him.

Think about that. The permit was harder to arrange than the cash.

This was the system. This was the India we built.

The Crime of Success

When you got an industrial license, your capacity was controlled. You got a license to produce, say, 10,000 cars per year. And here’s the thing:

It was a crime to produce more than your licensed capacity.

You could go to jail for making too many cars. For being too productive. For meeting too much demand.

Some of the famous “scandals” involving Reliance Industries in the late 1980s were about... producing too much. They exceeded their licensed capacity. That was the crime. Not fraud, not theft—success.

Remember: as late as 1980, India produced 30,000 cars annually. For 700 million people. There was a seven-to-eight-year waiting list for a Maruti. You paid bribes to move up the queue. And that was the modern India—the liberalized India after Maruti was introduced.

The Walmart Test

By the late 1980s, there were 836 items reserved for small-scale industries. This meant only businesses below a certain size could legally manufacture them.

What items? According to one economist: “Almost everything you buy in Walmart. Whether it is toys, whether it is furniture, apparel, footwear, many plastic items, cutlery. Basically, almost anything you use in the home.”

The logic was that large firms would outcompete small firms, destroying employment. So we banned large firms from making consumer goods.

The result: India couldn’t manufacture what its people wanted to consume. We couldn’t make toys for our children or shirts for ourselves—not at scale, not efficiently.

This is why the Raymond’s paradox exists today, which we’ll get to in Part 3. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The Hindu Rate of Growth

The results of all this brilliant planning:

India: 3.5% annual GDP growth

Pakistan: 5%

Indonesia: 6%

Thailand: 7%

Taiwan: 8%

South Korea: 9%

Economist Raj Krishna coined the term “Hindu rate of growth”—a joke so bitter it stuck. Only those expecting several cycles of reincarnation, he suggested, would tolerate such progress.

South Korea started the 1960s at roughly India’s income level. By 1991, Koreans were six times richer. Same starting point. Different policies. Different outcomes.

The Committees That Recommended More of the Same

Here’s the most infuriating part: India’s policy establishment knew the system wasn’t working.

Throughout the License Raj period, the government commissioned committee after committee to examine the control system. These committees would meticulously document all the problems—the delays, the corruption, the strangled enterprise, the perverse incentives. Brilliant reports. Devastating diagnoses.

Then, in their recommendations, they would call for... tighter controls.

“Very interesting,” one economist recalled. “They documented very well, actually... but most of them after having documented the problems, they would then recommend a tightening to say that, ‘Look, yes, these are problems, but we should function much better and more efficiently in doing these things.’”

The intellectual establishment couldn’t imagine dismantling controls. They could only imagine better controls. More efficient strangulation. More scientific suffocation.

Document the problems. Recommend more of the same. Repeat.

For forty years.

I’ve written before about my mother standing in the ration queue with her Lincoln’s Inn credentials, clutching her ration card like everyone else. The sugar full of stones. The kerosene smell. A UK-educated barrister who argued before the Supreme Court, waiting for her allotment of cooking oil like a supplicant.

This is what they were saving us from.

The Polyglot Novelist: P.V. Narasimha Rao (1921-2004)

Now let’s meet the men who fixed it.

Pamulaparti Venkata Narasimha Rao was born in 1921 in a tiny village near Karimnagar, Telangana—”a dusty speck in British India,” as one biographer put it. Farming family. Rural poverty. Colonial rule. Not the typical background for a revolutionary.

His education was voracious. Degrees from Bombay and Nagpur in arts and law. But here’s the absurd detail: 17 languages.

Nine Indian: Telugu, Hindi, Marathi, Urdu, Sanskrit, Bengali, Gujarati, Kannada, Tamil.

Eight foreign: English, French, Arabic, Spanish, German, Persian, Greek, Latin.

As one biographer noted: “While he spoke in 17 languages, the joke was he knew how to be silent in 17 languages.” Whenever Rao lost political power, he would go to JNU—Jawaharlal Nehru University—to learn another language. He picked up Spanish this way.

He was also a novelist. He translated Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” into Telugu. He wrote a 767-page roman à clef about Indian politics called The Insider. The reviews were... not kind. The Hindu called it “an 833-page infliction.” But he left a personal library of 10,000 books.

Here’s the Dave Barry detail: in his 60s, Rao taught himself COBOL, BASIC, and Unix programming. At 80, when doctors prescribed stress balls for his arthritic fingers, he typed documents instead.

Imagine your grandfather learning to code. Then becoming prime minister. Then saving the economy.

But don’t mistake the intellectual for a softie. Before politics, Rao trained as a guerrilla fighter against the Nizam of Hyderabad. On August 15, 1947—Indian Independence Day—while the rest of India celebrated, Rao was still fighting in a forest, evading an army with orders to shoot freedom fighters on sight.

This was not a soft man. He’d survived worse than opposition MPs and angry editorials. He could survive this too.

The crucial character insight comes from his biographer Vinay Sitapati: “He didn’t have strong views on the economy. To the extent he had socialist views, basically he flipped on a dime in June 1991.”

This wasn’t weakness—it was intellectual honesty. Rao read the evidence, understood the emergency, and changed his mind. In Indian politics, where ideological rigidity is often mistaken for principle, this was almost unique.

What Rao DID have was intellectual curiosity and tactical genius. After becoming prime minister, he spent the first week reading everything he could find about economics. Not political briefings—actual economic analysis. He wanted to understand for himself, not be told what to think. Then he assembled exactly the right team.

His political style was distinctive: silence. He rarely gave interviews. He never explained himself. He let his opponents wonder what he was thinking while he outmaneuvered them. “Silent Rao,” they called him—sometimes as criticism, sometimes as grudging respect.

And here’s the key detail: Rao had been the Industry Minister before becoming Prime Minister. He knew exactly what powers he was giving up.

“It is unlikely,” observed one economist who worked with him, “that had he been industry minister, that he would have agreed to give up all these powers.” But because he’d moved up—because he was now PM—he could dismantle the empire he’d once ruled.

This is not how it usually works. Usually, people protect their former fiefdoms. Rao didn’t.

The definitive assessment: “Had Manmohan Singh not become Finance Minister, liberalization would likely still have happened. Had Rao not become Prime Minister, India would be a different country.”

The Partition Refugee: Manmohan Singh (1932-2024)

Manmohan Singh was born in 1932 in Gah village, Punjab—now Pakistan. His father was a clerk for dry fruit importers.

The absurd detail: young “Mohna” (his childhood nickname) had pockets perpetually stuffed with dried fruits from his father’s trade. Childhood friends remembered a shy, brilliant boy. When he hesitated to join games, they would literally throw him into the village pond to loosen him up.

Then came Partition.

Singh was 15 when the telegram arrived: “Mother Safe, Father Killed.”

His grandfather Sant Singh had been murdered in the violence. The family house was burned. His matriculation exam results from Peshawar were never declared—riots had consumed the examination board. He had to retake the test a year later.

Years afterward, when Pakistani leaders invited him to visit his ancestral village, Singh declined.

“Yadan bariyaan talkh hun,” he said in Punjabi. The memories are very bitter.

In 2008, a childhood friend—Raja Mohammad Ali—visited him in Delhi, bringing soil and water from their village. Singh gave him a turban, shawl, and watches. He wrote a letter in Urdu expressing gratitude. He received famous Chakwali shoes from villagers. His doctors warned against eating the local cheese dish, but he couldn’t resist.

He never returned to Gah. The memories remained too bitter.

What he did instead was study with ferocious intensity.

Panjab University: First in BA Economics, first in MA Economics.

Cambridge (1955-57): The only First in economics that year. He won the Adam Smith Prize—previously won by John Maynard Keynes himself.

The poverty detail: he took cold showers in bitter Cambridge winters rather than pay for hot water. He lived on the cheapest meals available. He walked instead of taking buses. Everything saved was everything earned. For the rest of his life, he wore Cambridge blue turbans as tribute to those years—a Sikh refugee from a destroyed village, honoring the English university that had recognized his brilliance when no one else would.

Oxford: DPhil.

His intellectual formation was complex. He studied under Joan Robinson, the left-Keynesian who openly admired Maoist China. “She made me think the unthinkable,” he later said. But he was more influenced by Nicholas Kaldor, who demonstrated that “capitalism could be made to work.”

Here’s the twist: Singh’s Oxford doctoral thesis actually criticized India’s inward-looking trade policy—thirty years before he dismantled it. He later declared “great admiration” for Margaret Thatcher.

The seeds of 1991 were planted in those cold Cambridge rooms.

“People say I was an accidental Prime Minister,” Singh observed near the end of his life, “but I was also an accidental Finance Minister.” Rao picked him after others declined.

Why Singh was essential, according to those who worked with him: “The great advantage of Manmohan Singh being there as finance minister” was that he didn’t need to be briefed. When a typical politician becomes minister, civil servants have to explain everything from scratch. The minister then has to decide: Do I trust these guys? Are they ideologically motivated? Can I take this risk?

Singh didn’t need any of that. Commerce Ministry, Finance Ministry, Reserve Bank of India, Chief Economic Adviser, Planning Commission—he’d worked in all of them. “All this was totally internalized.”

“I may give him advice,” one economist recalled, “but he knows it anyway.”

The World Bank Prodigy: Montek Singh Ahluwalia (1943-)

Montek Singh Ahluwalia was also born in what became Pakistan—Rawalpindi, 1943. His father was a clerk.

Two of the three architects were refugees from Partition. Both were Sikhs.

The irony writes itself: Partition created the trauma that created the reformers.

Ahluwalia’s education was stellar even by Indian standards: Delhi School of Economics, then Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, then President of the Oxford Union debating society. The Oxford Union is where ambitious young Brits practice becoming prime ministers. Ahluwalia didn’t just participate—he ran the place. This man could argue anyone into the ground, and frequently did.

At 28, he became the youngest Division Chief in World Bank history, heading the Income Distribution Division. He spent eleven years in Washington, absorbing international development economics, watching the East Asian miracles up close—Korea, Taiwan, Singapore. He saw what worked. He saw what India was missing.

Then he did something unusual: he came home.

Most Indians with his credentials stayed abroad. The brain drain was real—why return to a country that taxed you at 97.75% and made you beg for permission to start a business? But Ahluwalia came back. He wanted to fix the system, not escape it.

In May 1990, Prime Minister V.P. Singh asked Ahluwalia a simple question: Why had Southeast Asian countries outperformed India?

Ahluwalia’s answer: “Because they had been much bolder in undertaking structural reforms.”

Singh asked him to write a paper.

One month later, Ahluwalia produced “Restructuring India’s Industrial and Trade Policies.” It leaked to the press and was dubbed the “M Document” (M for Montek).

This document matters enormously, for one reason: it proves the 1991 reforms were home-grown, not IMF-imposed.

The M Document was written in May 1990—a full year before the crisis. Before any IMF arrangement was contemplated. The blueprint existed long before the emergency.

When crisis hit, the reformers weren’t improvising. They were executing a plan that had been developed, debated, and refined over years. Ahluwalia later claimed they changed India’s trade policy in eight hours—because the thinking was already done.

The self-effacement was characteristic. “He [Manmohan Singh] was the principal architect,” Ahluwalia always insisted. His 2020 memoir is literally titled Backstage. He could have called it I Saved India. He called it Backstage.

The technocrat’s curse: politicians get credit, policy drafters get footnotes.

The Perfect Storm

By June 1991, everything was collapsing simultaneously.

May 21: Rajiv Gandhi assassinated by a suicide bomber during an election campaign in Tamil Nadu. A woman approached him with a garland, bent to touch his feet in traditional greeting, and detonated a bomb strapped to her body. The charismatic leader who was supposed to carry India into the 21st century—dead at 46.

Political chaos followed. Congress had no clear leader. The election had to continue despite the trauma. The party stumbled into power more from sympathy votes than mandate.

Rao emerges as a compromise candidate. He’s 70 years old, seen as a transitional figure—a caretaker who would keep the seat warm for the next generation. He leads a minority government with no mandate for anything, let alone revolution. Most observers expected paralysis, drift, more of the same.

Meanwhile, the external shocks keep coming:

The Soviet Union is collapsing—India’s largest trading partner and geopolitical ally, gone. Forty years of carefully cultivated relationships with Moscow, suddenly worthless. The trade credits that had kept India afloat, vanishing.

The Gulf War has spiked oil prices by 130%—from $15 to $35 per barrel. India imported nearly all its oil. Every dollar increase meant billions more in the import bill.

Moody’s has downgraded India’s credit rating. Commercial lending is frozen.

The World Bank has discontinued assistance, pending reforms India had always refused.

Foreign debt: $72 billion.

Foreign reserves: $1.2 billion.

Inflation: 17%.

The gold has been airlifted. The IMF emergency loan of $2.2 billion has been secured—barely, humiliatingly, with conditions attached.

Every external lifeline is snapping at once. It’s not one crisis—it’s a cascade, each failure amplifying the others.

Rao makes his move. He appoints Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister and gives him one instruction:

Fix this.

Then he provides political cover.

The famous exchange, as Rao appointed Singh: “If the reforms succeed, we both will claim the credit. If they fail, I will blame you and sack you.”

He was laughing when he said it. But only partly.

The Precipice

So there they stood.

The precipice was visible. A Hindu politician from a dusty village in Telangana who spoke 17 languages and wrote novels nobody wanted to read. A Sikh economist from a village that no longer existed, who took cold showers at Cambridge and kept dried fruits in his pockets. Another Sikh economist who’d been the youngest division chief in World Bank history and wrote a memo that would change a country.

Three men. All products of a civilization that absorbs contradictions—that somehow fits Hindus and Sikhs and Muslims and Christians and Jains and Buddhists and Parsis into one impossibly diverse democracy. A civilization where, as I’ve written before, any statement you make is true, AS IS its opposite.

India was bankrupt. The gold was gone. The Soviet model they’d followed for forty years was collapsing in real time. Every assumption that had guided Indian economic policy since independence was being revealed as catastrophically wrong.

The intelligentsia still believed in socialism. The party cadres still worshipped Nehru’s memory. The opposition would scream about selling out to foreign powers. The bureaucracy would resist losing its control. The protected industries would fight to keep their monopolies.

But the three men had something their opponents didn’t: a plan. The M Document—the years of thinking—the technocratic expertise accumulated across decades. They had political cover—Rao’s tactical genius, his willingness to let Singh take the heat while he worked the back channels. They had credibility—Singh’s Cambridge pedigree, Ahluwalia’s World Bank experience, Rao’s decades of political survival.

And they had something else: the crisis itself. The one thing that could break through forty years of socialist inertia. The emergency that made the previously impossible suddenly necessary.

Every other attempt at reform had been blocked, delayed, diluted, destroyed. But you can’t block the guy who’s keeping you from defaulting. You can’t delay the man who’s preventing famine. You can’t dilute the reforms when the alternative is collapse.

The crisis was terrible. The crisis was also the only opening they would ever get.

They were about to jump—and take India with them.

If you liked this, you will like my book, “The Science of Free Will” where I explore all kinds of cool stuff. Do bees have emotions? Why don’t we trade with ants? What is the future of AI?

Next: How they jumped.

The India Paradox is a series exploring how the world’s most diverse democracy somehow functions despite—or perhaps because of—its beautiful contradictions. Previous posts have covered everything from wedding negotiations to reservation politics, cricket economics to exam madness, gods in the machine to the gender paradox.

[All previous posts available at samirvarma.substack.com]

I know very little about the history of India. I read this like a novel I couldn’t put down. Thank you for writing it.

What an insightful writeup sir. Had a vague idea about our socialist policies but didn't know it was so strangulating.