The Forgetting

How India Buried Its Saviors—And Why It Matters

Here’s what the 1991 reforms did not change about my life:

I was already in America. I already had my PhD. I already had my career path. The reforms didn’t get me a job or make me rich. By the time they happened, I had escaped—physically, economically, psychologically. India’s transformation was something I watched from afar, like news from a country I used to know.

Here’s what the 1991 reforms did change:

I no longer cringed at being identified as Indian.

That’s it. That’s the thing. And if you’ve never felt that cringe, you won’t understand why this matters. But if you have—if you know what it’s like to hear “Where are you from?” and feel your stomach tighten—you’ll understand everything.

For decades, being identified as “Indian” abroad meant you were from a fifth-rate, uncivilized, basket case of an economy. You were from a genuine, no-fakes, absolute “shithole country”—except it was MUCH worse. At least shithole countries are small enough to ignore. India was big enough to be pitied. Big enough to be a punchline. Big enough that everyone had an opinion, and none of the opinions were good.

When people asked where you were from, you’d mumble “India” and change the subject. Or emphasize that you’d left, as if to say: I escaped. I got out. Don’t associate me with... that. I’m not really from there. Not anymore.

The news about India was always starving children or riots. Famines or assassinations. Disasters or dysfunction. A billion people trapped in poverty, governed by socialists who couldn’t keep the lights on. Never anything else. Because there wasn’t anything else.

That changed. Not overnight—it took years, maybe decades. But sometime in the 2010s, I noticed I didn’t cringe anymore. India was in the news for startups, for IT, for growth, for space missions, for Bollywood, for yoga studios in Brooklyn. It still had problems—massive, heartbreaking problems. But it was no longer only problems. It was no longer only pity.

I could say “I’m from India” without the internal wince. Without the reflexive need to distance myself. Without the shame.

I owe that to three men I didn’t know existed in 1991.

This post is about why India forgot them. And why that forgetting is wrong.

The Raymond’s Shirt: A Parable

Before we discuss the forgetting, one more absurdity. One more proof that the India Paradox never ends.

Rakesh Mohan—the economist who helped dismantle the industrial licensing system, who mapped the regulatory labyrinth so it could be torn down—bought a shirt recently. Nice cotton shirt. Raymond’s brand. About 3,000-4,000 rupees. Maybe $40-50 in American money.

Raymond’s is an iconic Indian company. Vertically integrated. Been around since 1925. Makes everything from thread to finished garments. If any Indian company should be able to manufacture a shirt domestically, it’s Raymond’s. They have the factories. They have the expertise. They have nearly a century of experience.

He went home. Checked the label.

Made in China.

A legendary Indian textile company, with complete domestic manufacturing capability, imports cotton shirts from China to sell in India.

“You can’t tell me they can’t manufacture a shirt which you can sell for 3,000, 4,000 rupees, which is made in India. I don’t understand this.”

This is the ghost of the small-scale reservations. Apparel was reserved for small-scale industries until the 2000s. Large companies couldn’t manufacture domestically at scale—it was literally illegal. They could make fabric, but not shirts. They could employ thousands in mills, but not in garment factories. For twenty years after 1991, this absurdity continued.

By the time de-reservation happened, supply chains had moved. China had built the factories. Bangladesh had built the expertise. Vietnam had captured the contracts. The jobs that should have employed Indians employed others. The manufacturing base that should have developed in India developed elsewhere.

India missed the manufacturing revolution that lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty in East Asia. It went straight from agriculture to services, skipping the middle step. And now a Raymond’s shirt—Raymond’s!—is made in China.

The 1991 reforms were incomplete. This shirt is proof.

But the reforms still matter. Because the alternative—the India where you couldn’t even import a decent shirt, where you waited years for a car, where producing too much was a crime—was worse. Much worse.

The incomplete revolution is still better than no revolution at all.

The Gate That “Doesn’t Open”

P.V. Narasimha Rao’s funeral cortege arrives at Congress headquarters, 24 Akbar Road, New Delhi.

The gates are closed.

Party officials explain: “The gates don’t open.”

Not metaphorical gates—physical gates. Iron gates. At the headquarters of the party Rao had led. On the day of his funeral. While his body waited outside.

The gates had opened for other Congress leaders in the past. But for the man who saved India from bankruptcy, who gave Congress its only full-term government between Rajiv’s assassination and 2004, who transformed the Indian economy more than anyone since independence—the gates “don’t open.”

His body was not allowed inside.

Eventually, after much embarrassment, arrangements were made. A quick memorial. Minimal honors. The cortege moved on. The Congress party had made its point: Rao was not “family.” Rao was not to be remembered. Rao’s achievements were not to be celebrated.

It would be easy to blame dynasty politics. This is the standard story. The Gandhis suppressing a non-Gandhi who had dared to succeed without them. Blah Blah Blah. Rao was never to be forgiven for proving that Congress could govern without a Gandhi at the helm. Blah Blah Blah. His success was an implicit rebuke to the family’s claim of indispensability. Blah Blah Blah. Etc and on and on. Boring! Also, crap.

But that explanation is too simple. It’s a “just so” story that explains the symptom, not the disease.

If dynasty politics were the whole answer, the BJP would have rehabilitated Rao to embarrass Congress. Other parties would have claimed him. The intellectual class would have pushed back. Someone would have said: this is wrong. Someone with a platform would have remembered.

The real reasons for the forgetting are deeper. And they’re not unique to India—they’re human. Which makes them harder to fix.

Why India Forgets

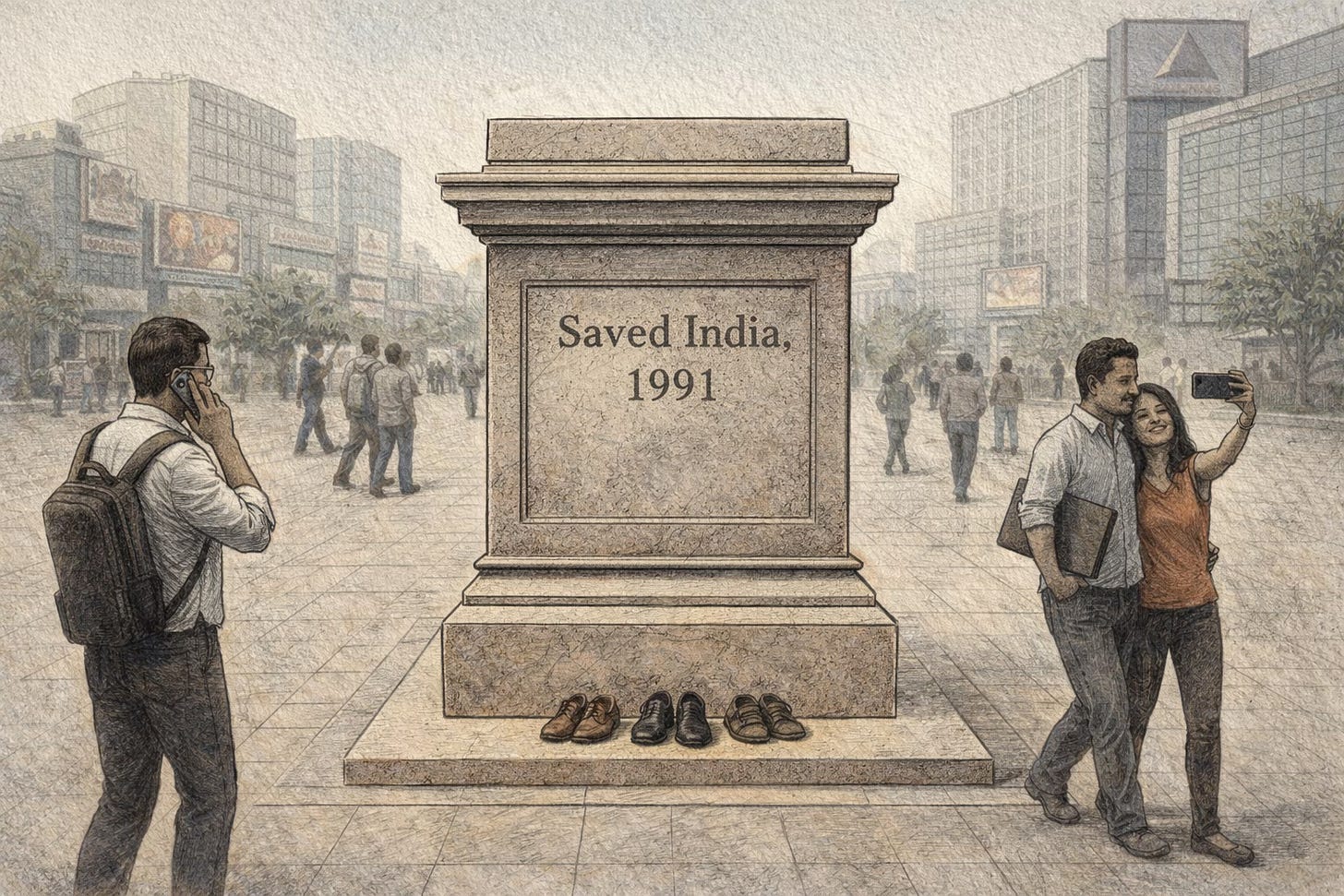

1. The Invisibility of Prevented Catastrophes

This is the deepest explanation, and it’s not Indian—it’s universal. It’s baked into how human memory works.

You cannot feel gratitude for something that didn’t happen.

The 1991 reforms prevented:

- Soviet-style economic collapse (remember what happened to Russia in the 1990s?)

- Possible mass famine (India was weeks from being unable to import food).

- Political fragmentation of a nuclear-armed state (India could have Balkanized).

- A generation of deeper poverty (another decade of 3.5% growth would have been catastrophic).

- The humiliation of permanent dependency on foreign aid.

- The brain drain accelerating until no one capable was left.

But because these didn’t happen, they’re not real to anyone. You can’t photograph the famine that didn’t occur. You can’t interview the refugees from the civil war that wasn’t fought. You can’t quantify the poverty that wasn’t endured.

The plane that didn’t crash. You don’t celebrate the engineer who prevented the disaster. You can’t point to a specific moment and say “there—that’s what they saved us from.” The counterfactual doesn’t have photographs. It doesn’t have victims whose stories can be told. It doesn’t have monuments or memorial days. It’s just... absence. An empty space where catastrophe would have been.

This isn’t an Indian problem. Americans don’t celebrate whoever prevented the 2008 financial crisis from becoming Great Depression II—assuming anyone did, assuming it wasn’t just luck. They barely remember Paul Volcker taming inflation in the 1980s—an achievement that made possible two decades of American prosperity. They’ve already forgotten the pandemic response that prevented millions more deaths. This is how human memory works. We remember disasters. We forget the people who prevented them.

The successful prevention of catastrophe is the most thankless achievement in human history.

Rao, Singh, and Ahluwalia prevented a disaster. They did it so well that the disaster became unimaginable. And the unimaginable cannot be remembered.

That’s why India forgot them.

2. Democratic Noise

In China, the CCP can decree: “Deng Xiaoping saved China. His portrait goes here. This is the official story. Teach it in schools. Put it in textbooks. End of discussion.”

In India, there’s no authoritative voice. Congress says one thing. BJP says another. Regional parties say something else. Academics critique everyone. Journalists investigate everyone. Everyone has a platform. Everyone has an opinion. Everyone has a vote.

This is wonderful for democracy. It’s terrible for historical memory.

Credit gets contested. Then diluted. Then forgotten. The noise drowns out the signal. Thirty years later, nobody agrees on what happened, let alone who deserves credit.

China has heroes by decree. India has arguments by design.

3. Socialist Intellectual Residue

The people who write history—journalists, academics, intellectuals—were overwhelmingly trained in socialist frameworks.

JNU. LSE. Cambridge leftists. The Delhi School of Economics in its Marxist phase. The Indian intellectual class in 1991 was deeply hostile to market reforms. They saw liberalization as surrender, not salvation. As betrayal of Nehru, not rescue of India.

They wrote the first draft of history. And in that draft:

- The reforms were “IMF-imposed” (they weren’t—the M Document proves it)

- They caused inequality (ignoring that inequality rose from a higher base because poverty fell)

- They were “incomplete” (as if perfect reform was politically possible)

- They benefited only the elite (ignoring 400 million people lifted from poverty)

The heroes became villains in the dominant narrative. Or worse—they became footnotes to a story about foreign imposition and domestic suffering.

Remember the committees that documented problems and then recommended tighter controls? That mindset didn’t disappear in 1991. It’s still writing the history.

4. Policy Consensus

Here’s an irony: the reforms succeeded so completely that they became consensus.

Every government since 1991 has continued them:

- BJP under Vajpayee: accelerated privatization

- Congress under Singh: continued liberalization

- BJP under Modi: GST, Make in India, further opening

When policy becomes consensus, it stops being anyone’s achievement. It’s just... what we do now. The way things are.

Nobody campaigns on “I will continue the reforms of 1991.” They campaign on what comes next. The foundation becomes invisible because everyone builds on it.

Success erased the memory of who created it.

5. The Indian Heroic Template

Indian mythology celebrates:

- Suffering: Ram’s fourteen-year exile, the Pandavas’ humiliation

- Sacrifice: Bhishma’s lifelong celibacy vow, Karna’s tragic loyalty

- Martyrdom: Gandhi’s assassination, Bhagat Singh’s hanging

- Dramatic confrontation: Arjuna’s crisis on the battlefield

What does this template not include? Competent technocrats who quietly solved problems and went home.

Singh didn’t suffer publicly. Rao didn’t sacrifice visibly. Ahluwalia just... did his job well. They made it look easy. They didn’t create drama. They prevented drama—which is the opposite of what heroes do in Indian narratives.

They don’t fit the heroic template. In India, that’s not a hero. That’s a bureaucrat.

6. The Brahminical View: Why We Want AI But Not Plumbing

There’s a deeper cultural explanation, and it connects everything.

At Imperial College London in the 1960s, Rakesh Mohan was one of 90 electrical engineering students. Eight were “subcontinentals”—Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis.

For their graduating projects, almost everyone did physical apparatus projects—building actual engineering devices. Real things that worked in the real world.

Of the eight subcontinentals, all but one did software projects.

“We just don’t like doing things with our hands.”

This isn’t just about engineering preferences. It’s about what we value. Mohan calls it “the Brahminical view that we should only do AI.”

India wants to be a knowledge economy—but can’t provide clean water to its cities. Wants to lead in artificial intelligence—but can’t manufacture a cotton shirt. Wants prestigious industries—but treats municipal corporations as beneath dignity. Wants to be Vishwaguru (world teacher)—but can’t fix the sewage systems.

At a panel in Bombay, Mohan sat next to Narayana Murthy, the founder of Infosys. He asked the audience of 1,000 students:

“Raise your hand if you would like to work in the municipal corporation of Mumbai.”

Zero hands.

“Now tell me how many people want to work doing useless things with Narayana Murthy?”

Half the hands went up.

Economic reform: boring. Heroic entrepreneurship: exciting. Government service: beneath dignity. Building Infosys: aspirational.

This is the cultural hierarchy that shapes what India remembers. The reformers of 1991 were technocrats who believed in getting things done. They fixed the plumbing—metaphorically speaking. They made the boring systems work. They didn’t build glamorous startups or win Nobel Prizes. They made startups possible. They made India creditworthy enough that others could win Nobel Prizes.

That’s part of why they’re forgotten. They did the work that doesn’t generate Instagram followers. They were municipal corporation people in an Infosys culture.

7. Dynasty Politics

Yes, Congress has an incentive to minimize Rao’s achievements. Rao succeeded without the cadre’s blessings. He proved Congress could govern technocratically not via personality. That’s threatening to a party cadre that has organized itself around personalities rather than policies.

But if “personality politics” were the explanation, someone would have broken through. The BJP has governed for over a decade now. They could have rehabilitated Rao to embarrass Congress. They could have claimed the reform legacy for the broader non-Congress tradition.

They didn’t—until very recently, and even then, tepidly. The “personality” explanation is too neat. It explains 5% of the forgetting, not 95%.

The 2004 Miracle

Before I tell you what happened to the reformers themselves, let me tell you about something that happened in 2004—something that says more about India than all the forgetting, something that shows what this civilization is capable of when it works.

Congress won the election. Sonia Gandhi, the party president, was expected to become Prime Minister. She had led the campaign. She had the numbers. The job was hers.

She declined.

A Roman Catholic. Italian-born. Widow of Rajiv Gandhi, mother of Rahul. She had spent years building the party back from electoral defeats. She had the power to take the top job. She chose not to.

Why? Officially, because of the sacrifice tradition in the Gandhi family—following in the footsteps of her mother-in-law who declined the presidency. Unofficially, probably because an Italian-born Catholic PM would have created too much ammunition for opponents, too much distraction from governance.

Whatever the reason, she stepped aside. And she nominated Manmohan Singh—a Sikh.

Singh was sworn in as Prime Minister. The ceremony was presided over by President APJ Abdul Kalam—a Muslim, a scientist, a bachelor who lived simply and played the veena.

In a Hindu-majority nation (80%+).

A Roman Catholic voluntarily giving up power to a Sikh, in a ceremony presided over by a Muslim, in a Hindu-majority democracy. And no one in India commented on it.

I mean that literally. It was a non-story. The Financial Times had to point it out to Indian readers. Indians hadn’t noticed. It didn’t occur to anyone that this was remarkable.

Of course a Catholic could decline power. Of course a Sikh could become PM. Of course a Muslim could preside as President. What’s surprising about that? This is India. We do this.

Everything. Everything is remarkable about that.

Could this happen in Pakistan? A Hindu president swearing in a Christian prime minister nominated by a Sikh party president? Could this happen in Bangladesh? In Indonesia? In most Middle Eastern countries? In much of the world?

Muhammad Ali Jinnah—the founder of Pakistan—once criticized Gandhi’s syncretism, Gandhi’s claim to be Hindu AND Muslim AND Christian AND Jew. “Only a Hindu could say that,” Jinnah argued. He meant it as criticism. He was describing the absorptive, syncretic tendency he believed would swallow Muslim identity, erase minority distinctiveness.

But he was also describing something true about Indian civilization. Something that makes moments like 2004 possible. Something that made 1991 possible.

Two of the three architects of India’s economic salvation were not Hindu. Both Singh and Ahluwalia were Sikhs. Both were Partition refugees. And nobody cared about their religion. Nobody thought it relevant. Nobody mentioned it.

In 2022, Rishi Sunak became Prime Minister of Britain. Ethnic Indian. Hindu. He’d blessed a cow at a Hindu ceremony. Lit Diwali lamps at Downing Street. And no one cared.

This says something wonderful about Britain—that it too can absorb diversity, that the former colonizer has learned something from the former colony. It also shows that the tolerance can travel, that what India cultivated over millennia can take root elsewhere in decades.

Is this tolerance under threat in today’s India? Is BJP nationalism erasing the syncretism? I think the tolerance is hiding, not dying. Because five thousand years of absorptive civilization don’t disappear because of political noise. The underlying operating system is older than any government. It survived the Mughals. It survived the British. It will survive the BJP.

That’s what India is capable of. Now let me tell you how it treated the men who saved it.

The Three Fates

What happened to them? This is where the story gets painful.

Rao: The Shakespearean Tragedy

P.V. Narasimha Rao’s fall was swift, brutal, and—in retrospect—inevitable. The man who saved India from bankruptcy died in disgrace, forgotten by the party he’d rescued.

1992: The Babri Masjid was demolished on his watch. A Hindu mob destroyed a 16th-century mosque in Ayodhya while Rao’s government did nothing to stop them. He was blamed—by secularists for allowing it, by Hindu nationalists for not supporting it openly, by everyone for the paralysis that let it happen.

The truth is more complicated. Rao may have been outmaneuvered. He may have miscalculated. He may have believed promises that weren’t kept. But the result was the same: his secular credentials were destroyed, and the communal tensions that followed poisoned his legacy.

1996: Congress loses the election. Rao is blamed—for the Babri Masjid, for corruption allegations, for not being a Gandhi. The party that had benefited most from his reforms turned on him instantly.

1996-2000: Corruption trials. Allegations of bribery in a JMM (Jharkhand Mukti Morcha) vote-buying scandal. The man who saved India from bankruptcy spent his final years in court, defending himself from charges that he paid MPs to save his government.

Was he guilty? The legal record is contested. He was convicted, then acquitted on appeal. But the damage was done. The “taxi driver test”—what does an ordinary person remember about someone?—produces only scandals. Ask about Rao, and people remember corruption, Babri Masjid, disgrace. Not the reforms. Not the 400 million people lifted from poverty.

The erasure was thorough. His contributions were downplayed in official Congress party history. No major memorials in Delhi. No buildings named. His ashes weren’t even immersed in the Ganges with full honors—the family had to do it themselves, years later.

The late rehabilitation came too late. In 2024, Rao received the Bharat Ratna—India’s highest civilian honor. Awarded posthumously. Twenty years after his death. By a BJP government, not Congress.

Think about that. Honored by his opponents. Buried by his beneficiaries. The party he saved wouldn’t honor him. The party he defeated would.

Singh: The Tragedy of the Second Act

Manmohan Singh got something Rao never did: a second act. And it complicated everything.

2004: Congress wins the election. Sonia Gandhi declines to become Prime Minister. She nominates Singh instead. The reluctant reformer of 1991 becomes the unlikely Prime Minister of 2004.

2004-2014: He served as PM, leading India through its fastest growth years. GDP growth hit 9%. The nuclear deal with the United States transformed India’s global standing. He won re-election in 2009—something few predicted.

For a while, it looked like vindication. The quiet reformer was now running the country. The architect of 1991 was in charge of the next phase.

Then the second term happened.

His reputation as the “Silent PM” became a liability. He rarely spoke to the press. He let ministers speak for him. In a media environment that rewarded performance and punished reticence, his silence looked like weakness.

His second term was mired in scandals—the 2G spectrum allocation, where telecom licenses were allegedly sold at artificially low prices. The coal block allocations, where mining rights were distributed opaquely. Corruption allegations swirled around colleagues, and Singh wouldn’t dismiss them. Whether this was loyalty, paralysis, or constraint by coalition politics—historians will argue. But the effect was clear.

By 2014, the “Silent PM” had become a punchline. The BJP’s campaign mocked him relentlessly. Narendra Modi promised “minimum government, maximum governance”—an implicit contrast with Singh’s perceived passivity.

The BJP won a landslide. Singh left office diminished, his reputation in tatters.

His final public statement, in January 2014: “I honestly believe that history will be kinder to me than the contemporary media.”

He was right.

December 26, 2024: Singh died at 92. State funeral with full honors. Twenty-one-gun salute. Seven days of national mourning. Tributes poured in from across the political spectrum—including from the BJP leaders who had mocked him.

In death, he was remembered as the reformer of 1991, not the silent PM of 2010. The second act faded. The first act endured. History was kinder.

One detail haunts me: He never returned to Gah. His birthplace, now in Pakistan. The village where his grandfather was murdered during Partition. Where his childhood home was burned. Where his family fled with nothing.

Pakistani leaders invited him to visit. He declined.

“Yadan bariyaan talkh hun,” he said. The memories are very bitter.

A friend from Gah visited him in Delhi in 2008, bringing soil and water from the village. Singh gave him a turban, a shawl, watches. Wrote him a letter in Urdu. Received the traditional Chakwali shoes and couldn’t resist the local cheese despite his doctors’ warnings.

But he never went back. The memories remained too bitter. The Partition refugee who saved India from one crisis never returned to the place where his own crisis began.

Ahluwalia: The Invisible Man’s Choice

The technocrat’s fate: footnotes.

Ahluwalia continued serving in various capacities—Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission, advisor to governments, respected voice on economic policy. He wrote his memoir in 2020.

He titled it Backstage.

Not I Saved India. Not The Architect of Reform. Backstage. The place where the real work happens, invisible to the audience.

The self-effacement was characteristic. “He [Manmohan Singh] was the principal architect,” Ahluwalia always insisted. Even in his own memoir, he deflects credit to others.

The technocrat’s curse: politicians get credit, policy drafters get footnotes. Ahluwalia chose the footnote. He seems content there.

But These Explanations Don’t Justify the Forgetting

Let me be clear: understanding why India forgets is not the same as accepting it.

The forgetting is wrong.

Not “understandable given complexity.” Not “one perspective among many.” Wrong.

The Counterfactual Test

Without Rao: Any other politician would have done the minimum. Protected socialist orthodoxy. Blamed external factors. Waited out the crisis with IMF loans and hoped for the best. The reform window would have closed.

Without Singh: A political Finance Minister would have compromised, lacked international credibility, watered down the reforms to please constituencies. The technical design would have been flawed. The execution would have been botched.

Without Ahluwalia: No blueprint. No M Document. No years of preparation. Ad hoc crisis response. Easy reversal when the pressure eased.

These three were indispensable. Not because others couldn’t help—they needed thousands of helpers, and they had them. But without these three as catalysts, the helpers would have had nothing to help with.

The Achievement Quantified

400-500 million people lifted from poverty

The largest democratic poverty alleviation in human history

GDP multiplied 16x in three decades

Life expectancy increased 9 years

Foreign exchange reserves from $1.2 billion to $700 billion

What else in the 20th century lifted this many people from poverty, democratically, without mass coercion?

Nothing.

The Marshall Plan rebuilt countries that already knew how to be rich. China’s reforms came with Tiananmen Square and the suppression of Uyghurs. The Soviet collapse didn’t produce reform—it produced oligarchy and eventually Putin.

India’s 1991 reforms are unique. And the men who made them happen are forgotten.

That’s not complexity. That’s ingratitude.

The Case for Remembering

India should remember these three the way:

- America remembers the Founders.

- China remembers Deng.

- France remembers de Gaulle.

- Europe remembers the architects of the EU.

The fact that India doesn’t is a failure of:

- Memory.

- Gratitude.

- Historical understanding.

- National self-respect.

It’s not “well, history is complicated.” It’s a mistake that should be corrected.

Remember Them

The three most important people of the late 20th century were:

A polyglot novelist from a dusty village in Telangana who learned to code at 60, who spoke seventeen languages and knew how to be silent in all of them, who trained as a guerrilla fighter against the Nizam of Hyderabad before becoming a politician, who read economics textbooks his first week as Prime Minister and told his Finance Minister to be bolder, who wrote a novel nobody wanted to read and governed a country nobody thought he could save.

A Partition refugee from a village that no longer exists who took cold showers at Cambridge to save money, who won the Adam Smith Prize (previously won by Keynes), who kept dried fruits in his pockets as a boy because his father worked for a dry fruit importer, who wore Cambridge blue turbans for the rest of his life as tribute, who wrote his doctoral thesis criticizing the very policies he would dismantle thirty years later, who never returned to his birthplace because the memories were too bitter, who spoke so softly you had to lean in to hear him announce a revolution.

A World Bank prodigy who became the youngest division chief in that institution’s history, who came back to India when everyone with his credentials was leaving, who wrote a memo that became a blueprint, who claimed to change trade policy in eight hours because the thinking was already done, who titled his memoir Backstage because that’s where he believed he belonged, who gave credit to everyone except himself.

They saved India.

They saved it not through heroic suffering or dramatic sacrifice, but through competence. Through preparation. Through the unglamorous work of understanding systems and changing them. They saved it by being good at their jobs when the moment demanded it.

In 1991, I was at the University of Texas, head down, working hard, trying not to think about India. Ashamed to be associated with a country that seemed to have no future. Cringing when people asked where I was from.

Today, I can say “I’m from India” without the internal wince. Three men I didn’t know existed made that possible.

They gave 500 million people the chance to escape poverty.

They proved that democratic reform is possible—that you don’t need authoritarianism to transform an economy, that you don’t need to shoot protesters in the square to open markets, that you can change a civilization’s trajectory through budgets and policy papers and quiet persistence.

They proved that crisis can be converted to opportunity, if you have a plan and the nerve to execute it.

India forgot them.

It forgot them because they succeeded—and success is invisible. It forgot them because they didn’t fit the heroic template—and quiet competence doesn’t make for good stories. It forgot them because the reforms became consensus—and consensus has no authors. It forgot them because the intellectual class that writes history was hostile to their achievement—and first drafts cast long shadows.

But the forgetting is wrong.

It’s not “complicated.” It’s not “a matter of perspective.” It’s wrong in the simple sense that ingratitude is wrong, that failing to acknowledge what you owe is wrong, that pretending the present created itself is wrong.

This series—this small corner of the internet—is part of remembering.

It’s not much. A few thousand words in a Substack that most of India will never read. But memory has to start somewhere. It starts with one person saying: I remember. I know what happened. I know who made it possible.

Remember them.

If you liked this, you will like my book, “The Science of Free Will” where I explore all kinds of cool stuff. Do bees have emotions? Why don’t we trade with ants? What is the future of AI?

This is Post 19 (in three parts) of The India Paradox series. We’ve examined how India manages its kaleidoscope of cultures, how this travels with the diaspora, the wedding wars, the economic transformation from socialism to capitalism, the WhatsApp uncles, the startup ecosystem, the food diversity, the language wars, gods in the machine, the gender paradox, the future of the past, Macaulay’s children, and the third rail of reservations. Now we’ve remembered the people who made the economic story possible.

[All previous posts at samirvarma.substack.com]

“There is no limit to the amount of good you can do if you don't care who gets the credit,” a quote attributed to both Harry S Truman and to Ronald Reagan, certainly applies to the example of the Indian “Triumvirate.”

Samir Varma’s focus is similarly devoid of self-aggrandizement. One suspects his riveting series will reap returns far beyond those being realized at the moment. Never underestimate the power of a planted seed.

This hit me hardest at the idea that we can’t feel gratitude for what didn’t happen. Love that you insist competence can be heroic. Not the dramatic kind we’re trained to worship, but the boring, systems-level work that actually saves lives at scale. This felt like a corrective to our whole cultural appetite for spectacle.