The Emperor Has No Alpha

What Data Mining Reveals About Academic Finance

A particle physicist’s take on why the peer review process might not be adding the value you think

Tyler Cowen flagged a paper on Marginal Revolution with a characteristically understated summary: “Finance theory is in even more trouble than we had thought.”

The paper is from the Federal Reserve Board. The title: “Does Peer-Reviewed Research Help Predict Stock Returns?”

The answer, after 56 pages of rigorous analysis: not really.

I’ve spent more than three decades in quantitative trading. Before that, I was a particle physicist at UT Austin, working under the incomparable ECG Sudarshan on quantum scattering theory (and Nobel Prize winner Steven Weinberg was on my dissertation committee). When the Superconducting Supercollider was cancelled in 1993, I pivoted to finance. I brought with me a physicist’s insistence that elegant theories must predict, not just explain.

This paper confirms what I’ve long suspected.

The Setup

The researchers—Andrew Chen, Alejandro Lopez-Lira, and Tom Zimmermann—did something audacious. They took 29,000 accounting ratios and mined them for statistical significance. Simple ratios like debt-to-assets. Scaled first differences like change-in-inventory divided by lagged sales. Nothing fancy. Just brute force computation against every possible combination.

Then they compared what emerged from this naive data mining against 212 peer-reviewed stock return predictors from academic journals. The prestigious ones. Journal of Finance. Journal of Financial Economics. Review of Financial Studies.

The peer review process for these papers typically takes five years. It involves professors from elite universities scrutinizing methodology, demanding robustness checks, evaluating theoretical foundations. If any process should separate signal from noise, this is it.

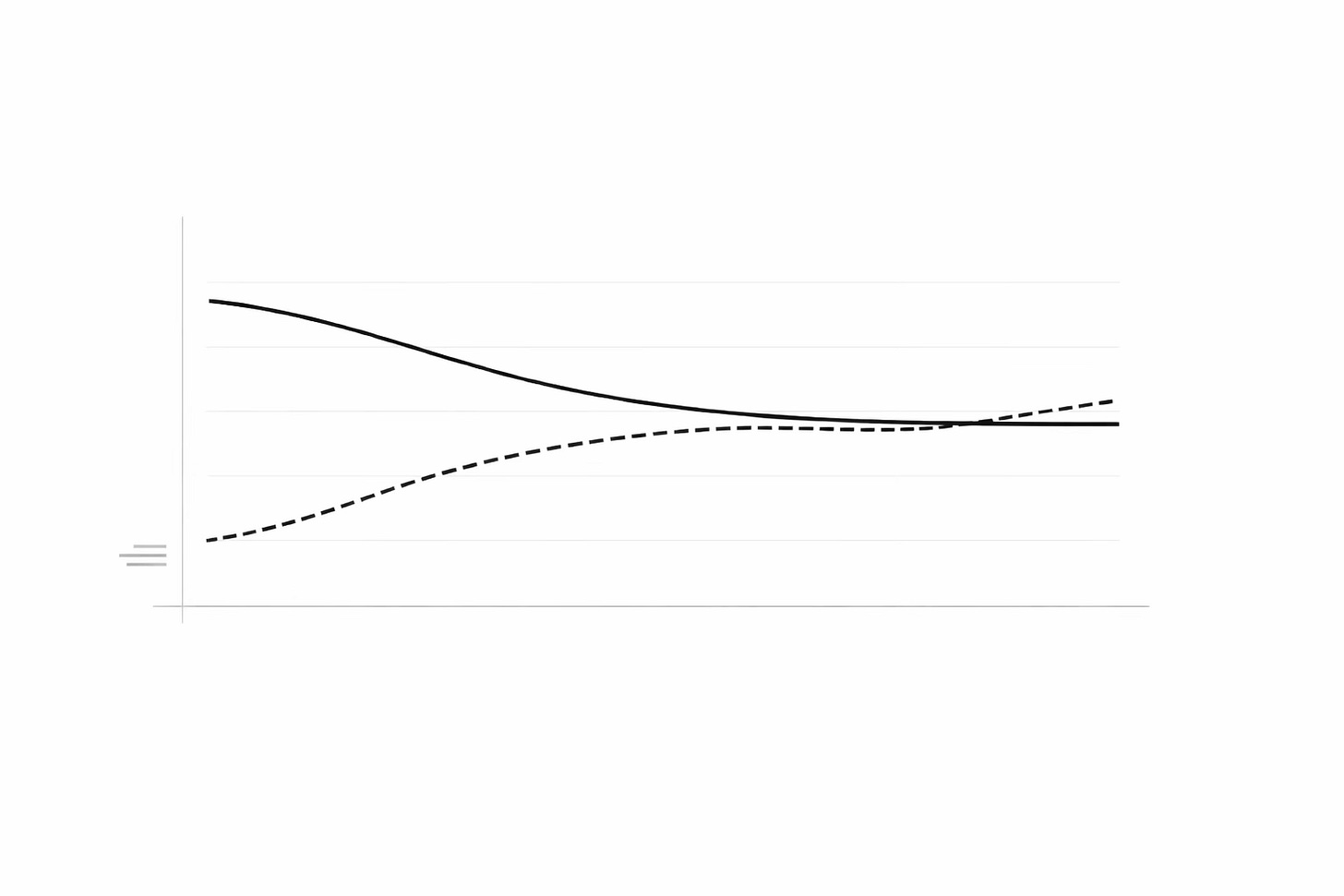

Here’s what they found: both approaches—the peer-reviewed research and the mindless data mining—retain about 50% of their predictive power out of sample.

The solid line is peer-reviewed research. The dashed line is data mining. They converge.

The Uncomfortable Finding

Let me state this plainly. A computer searching for t-statistics greater than 2.0 among accounting ratios performs approximately as well as decades of academic research.

This isn’t a marginal result. The paper tests this across multiple performance metrics:

Raw long-short returns: published predictors retain 56%, data-mined predictors retain something like 50-51%

CAPM-adjusted alphas: published 60%, data-mined 52%

Fama-French 3 + momentum alphas: data mining actually outperforms published research

The standard errors overlap. You cannot statistically distinguish peer-reviewed discoveries from computational brute force.

What About Theory?

Here’s where it gets interesting for someone with my background.

In physics, theory matters. The Standard Model predicted the Higgs boson decades before we found it. General relativity predicted gravitational waves a century before LIGO detected them. Theory constrains the search space. It tells you where to look.

The academic finance literature operates on a similar premise. Researchers don’t just find statistical patterns—they explain them. This predictor works because of risk compensation. That one works because of behavioral mispricing. The theory is supposed to separate genuine phenomena from spurious correlations.

The paper categorizes 173 predictor-papers by their theoretical foundations:

Risk-based explanations: 20% of predictors

Mispricing-based explanations: 61% of predictors

Agnostic (no theoretical stance): 20% of predictors

The results are brutal.

Risk-based predictors? They underperform data mining on most metrics. If markets compensate for risk, and academics identify these risks correctly, then the predictors should persist out of sample. They don’t.

Mispricing-based predictors? They perform about the same as data mining. The elaborate behavioral theories—investor overreaction, attention biases, limits to arbitrage—add no predictive value beyond what a computer finds by searching t-stats.

The only category that shows any sign of outperformance? The agnostic research. The papers that explicitly refuse to take a theoretical stance. These retain an additional 9-31 percentage points of performance depending on the metric.

Let that sink in. The less theory you have, the better you do.

This finding reminded me of something Peter Brown, co-CEO of Renaissance Technologies, said in Gregory Zuckerman’s The Man Who Solved the Market:

“If there were signals that made a lot of sense that were very strong, they would have long-ago been traded out. There are signals that you can’t understand, but they’re there, and they can be relatively strong.”

The Fed paper just provided the empirical confirmation. The patterns that persist are precisely the ones that resist explanation.

Even the Giants Fall

Perhaps you’re thinking: maybe the average academic paper isn’t that rigorous, but surely the foundational discoveries are different. The canonical findings. The ones with Nobel Prize winners behind them.

The paper tests this directly. They compare:

Fama and French (1992): Book-to-market ratio

Jegadeesh and Titman (1993): Momentum

Banz (1981): Size

These aren’t just published papers. They’re the papers. Fama and French reshaped how we think about asset pricing. Momentum has theoretical foundations from Hong and Stein, from Brav and Heaton, from multiple rigorous equilibrium models. Size has Berk’s theoretical framework plus decades of empirical confirmation.

The result? Data-mined alternatives perform comparably.

For Fama-French’s B/M: the original earned 61 bps/month post-sample. Data-mined alternatives? 65 bps/month.

For Banz’s size: the original earned 15 bps/month post-sample. Data-mined alternatives? 42 bps/month. The computers beat the Nobel Prize winner.

Momentum is the exception—the original earned 72 bps versus 52 for data-mined alternatives. One out of three.

What This Actually Means

I’m not saying academic finance is useless. I’m saying the peer review process may not be filtering for what we think it’s filtering for.

The paper suggests four implications:

1. Empirical evidence trumps theoretical evidence.

Having modern peer-reviewed theory supporting your predictor doesn’t improve post-sample performance. Even quantitative equilibrium models—the gold standard in academic finance—add no predictive value. The only thing that matters is whether the statistical pattern is real.

2. Investors don’t learn about risk from academic research.

If investors learned that certain characteristics proxy for systematic risk, they would demand compensation, and the premiums would persist. But risk-based predictors decay just like everything else. Either the risks identified by academia aren’t the risks real investors care about, or the whole risk-based framework is wrong.

3. Data mining works.

This shouldn’t surprise a physicist. Nature is what it is. If accounting ratios contain information about future returns, a computer can find that information. You don’t need a theory for gravity to predict where a ball will land.

4. Most cross-sectional predictability is probably mispricing.

The peer review process attributes 60% of predictability to mispricing and only 20% to risk. And the mispricing-based predictors decay over time—consistent with investors eventually correcting mispricings. The simpler explanation fits the data.

A Physicist’s Perspective

In my years running quantitative strategies, I’ve read tens of thousands of academic papers. Some have been useful. Many have not.

What I take from this research is not nihilism. It’s calibration.

The peer review process is good at ensuring reproducibility. If a paper says a predictor earned significant returns in a specific sample, that’s probably true. The CZ dataset the paper uses confirms this—their t-stats match the original papers.

What peer review doesn’t do is ensure post-sample robustness. It doesn’t separate stable phenomena from transient ones. The elaborate theories—risk compensation, behavioral biases, information asymmetries—don’t predict which effects will last.

What does predict persistence? The strength of the in-sample evidence. If you find a t-stat of 4.0 instead of 2.0, you’re more likely to find something real. The data speaks for itself.

The paper’s final observation is telling. Data mining could have discovered most of the major themes in asset pricing—investment, accruals, external financing, earnings surprise—before they were published. Sometimes decades before.

Graham and Dodd wrote Security Analysis in 1934. The idea that accounting ratios predict returns is almost a century old. We didn’t need modern theory. We needed data.

What I Tell People Who Ask for Advice

Over the years, many aspiring traders have contacted me for guidance. I tell them all the same thing:

Learn all of it. The academic literature. Finance theory. Economics. The MBA curriculum. Read the papers. Understand the models. Know what Fama and French are saying, what the behavioral economists claim, what the market microstructure people believe.

But here’s the crucial part: once you understand what they’re saying, your job is to figure out why they’re wrong.

It is in that why that you will find your durable competitive advantage as a trader. Whatever it might be.

This paper illuminates the path. The academics aren’t lying to you—their findings are statistically valid in-sample. The peer review process confirms reproducibility. But reproducibility isn’t the same as persistence. Understanding the gap between what academics measure and what actually works going forward is where edge lives.

And there’s one more thing, perhaps the most important thing: that durable competitive advantage needs to be 100% congruent with your own personality.

Otherwise you will never be able to trade it. You will chicken out at exactly the wrong moments.

I’ve seen it countless times. Someone develops a perfectly valid strategy that doesn’t fit who they are. A risk-averse person tries to trade momentum. A patient value investor tries to scalp. A quantitative thinker tries to trade on intuition. They can’t execute when it matters because every fiber of their being is screaming that something is wrong.

Your edge must be yours. Not borrowed. Not copied. Not theoretically optimal for some abstract investor. Yours.

The only way to get congruence with your personality is sheer hard work. Nothing more. And nothing less. You have to test, test, test and test. Then test some more. Test until you’re sick of it. Then test some more. Then test until you want to throw up (and indeed do throw up). Then test some more. You have to have unshakable confidence that what you are doing is correct. Otherwise, forget it. Find an easier profession. This one isn’t easy.

Oh, and by the way, no matter how much you prepare, test, read, paper-trade, think, etc., you are going to lose money at the beginning unless you are exceedingly lucky. That’s just how the trading process works. You pay bucketloads of money in tuition to become a doctor or a lawyer or an accountant. Your bucketload here is your losses. Claim them. Live with them. Be upset with them. But then, learn from them. As Yoda might say, “there is no other way.”

The data mining result in this paper is liberating in this sense. It means you don’t need to genuflect before academic authority. You need to understand the academics, yes. But then you need to find what works for you, validated by data, congruent with your psychology.

That’s a much harder problem than reading papers. It’s also the only problem that matters.

Practical Takeaways

If you’re a retail investor:

Don’t assume a strategy works because it has academic backing

Look at post-publication performance, not just in-sample results

Simple is often as good as complex

Be skeptical of elaborate theoretical justifications

If you’re a quant:

Data mining isn’t a dirty word—it’s what everyone is actually doing

Theory should follow data, not precede it

The best predictor of future performance is statistical strength, not theoretical elegance

Most alpha decays; position accordingly

If you’re an academic:

The paper ends with a question that should haunt the profession: “Does peer-reviewed research help predict stock returns?”

The answer is yes—but not more than a computer running t-tests.

This is part of an occasional series on quantitative finance and academic research. For more on my background, see my recent interview with Titans of Tomorrow. My book, The Science of Free Will, is available now.

References:

Chen, Andrew Y., Alejandro Lopez-Lira, and Tom Zimmermann. “Does Peer-Reviewed Research Help Predict Stock Returns?” Federal Reserve Board Working Paper, December 2025. arXiv:2212.10317v7

If you found this valuable, consider sharing with someone who believes in efficient markets—or someone who thinks academic finance has all the answers. The truth, as always, is messier.

I don’t know the peer review process well so I will not argue with your conclusion on that dimension. I will say that finance and business theory are not good at predicting or at offering solutions in the real world. No amount of data and research will change that. With larger data sets it may be mitigated a little but only a little. For some reason, people seem to think AI will “solve” this - it won’t.

Thanks for the article. Really good takeaways, Samir…stick to strengths and stay consistent with who you are. It resonates well.