Gravity's Fingerprint on Quantum Interference

A new way of using the double-slit experiment to learn about nature

My very old and dear friend Arie Kapulkin and I did some work recently that I think will be of interest: a new way of considering what the “double-slit” experiment can tell us about Nature.

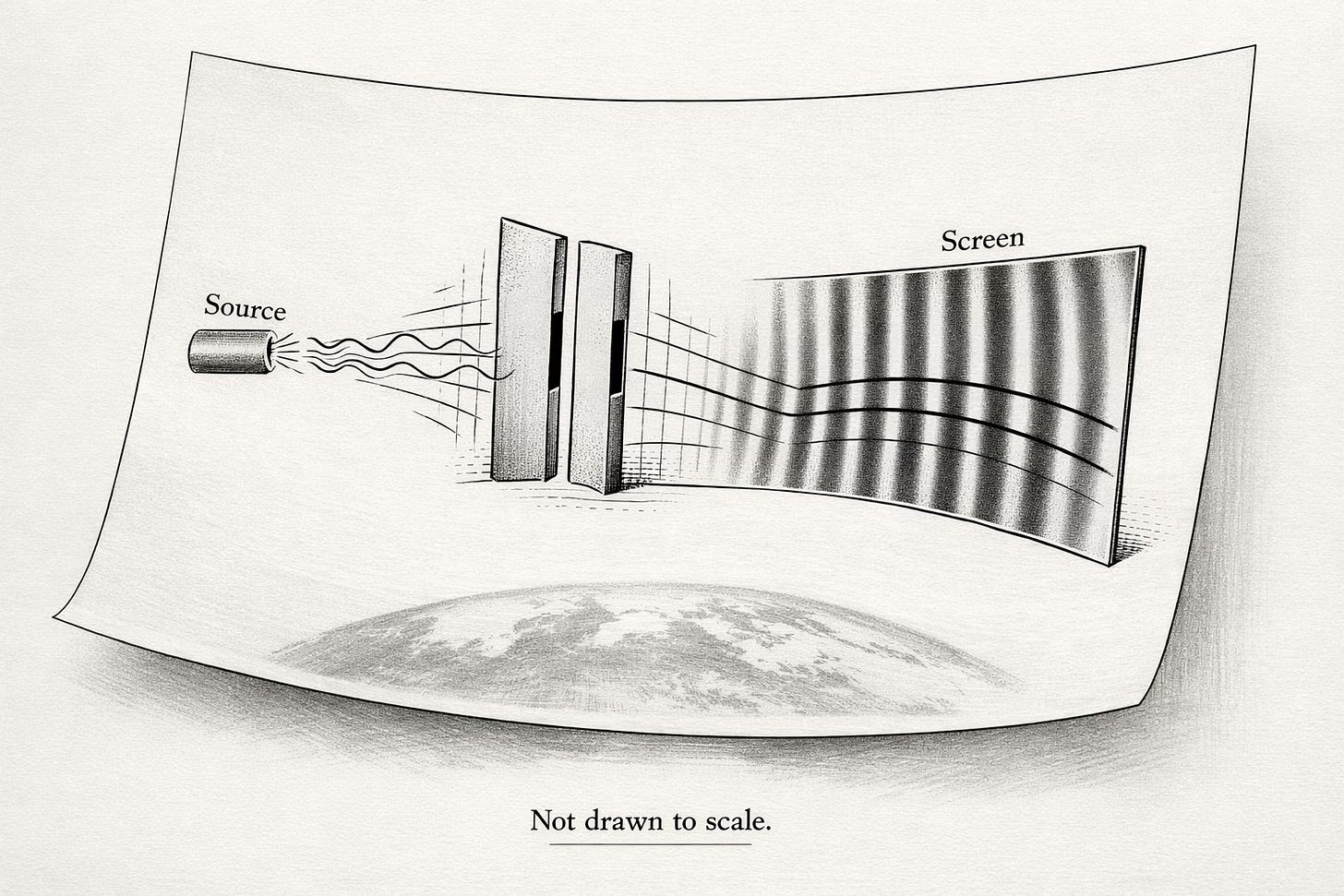

The double-slit experiment has a long history. Thomas Young’s original optical version dates to 1801. The wave nature of matter was demonstrated in the 1920s through electron diffraction, but the iconic quantum version—where individual electrons or neutrons build up an interference pattern one by one, each particle seemingly interfering with itself—came later: electron double-slit experiments in the 1960s, neutron interferometry in the 1970s, and strikingly clear single-electron demonstrations in the 1980s. It has since become the canonical illustration of quantum mechanics.

Feynman famously called it “the only mystery.” Textbooks use it to introduce superposition, wave-particle duality, and the measurement problem. It’s the experiment everyone reaches for when trying to convey quantum strangeness.

But there’s something every textbook version quietly ignores: we don’t live in flat spacetime. The experiments happen on Earth, in a gravitational field, where clocks tick at slightly different rates depending on height, where spacetime is curved by the mass beneath our feet. What happens to quantum interference when you actually account for gravity?

This question sits at the intersection of our two deepest theories of physics. And as Arie and I show in a recent paper, the answer turns out to be remarkably precise—even if the effects are, for now, unmeasurably small.

What’s Actually Going Through the Slits?

Before we can talk about gravity’s effect on interference, we need to clear up a misconception that creates artificial mystery.

Popular accounts describe the double-slit experiment something like this: an electron is fired at a barrier with two slits, and “somehow” it goes through both slits at once, interfering with itself on the other side. If you try to determine which slit it went through, the interference pattern disappears. Spooky. Mysterious. Quantum weirdness.

This framing makes the phenomenon seem more puzzling than it needs to be. The problem is the picture: a tiny billiard ball that “somehow knows” about both slits. Once you’re imagining a little particle—a thing with a definite location—you’re forced into contortions explaining how it can be in two places at once.

The resolution comes from quantum field theory, and it requires understanding what a field actually is.

What is a field?

A field is simply a quantity that has a value at every point in space (and time). That’s it. Nothing mystical.

Temperature in a room is a field: at every point in the room, there’s a number telling you how hot it is. The temperature might be 22°C near the window, 24°C by the radiator, 21°C in the corner. One number at each location.

Wind velocity is a field too, but now you need three numbers at each point: the wind’s speed in the x-direction, the y-direction, and the z-direction. A vector field.

The electromagnetic field requires six numbers at each point: three components for the electric field, three for the magnetic field. These six numbers, assigned to every point in spacetime, constitute “the electromagnetic field.”

(A note on terminology: mathematicians (such unreasonable people) use the word “field” to mean something completely different—algebraic structures like the real numbers or complex numbers. This is an unfortunate historical collision. When physicists say “field,” they mean a quantity spread over spacetime. Context usually makes it clear, but it’s worth flagging.)

What is a field theory?

A field theory is the set of rules—expressed as differential equations—that govern how these numbers change.

The rules typically say: the value of the field at one point depends on the values at neighboring points. Change the field somewhere, and that change propagates outward, affecting nearby regions, which affect their neighbors, and so on.

Maxwell’s equations are the field theory for electromagnetism. They tell you how those six numbers at each point evolve in time, given the numbers at surrounding points. If you wiggle a charge here, the disturbance ripples outward through the electromagnetic field—and we call that ripple “light.”

The conceptual revolution of quantum field theory

Here’s the key insight: quantum field theory says everything is a field.

There’s an electron field permeating all of spacetime, right now, everywhere—including the space you’re sitting in. What we call “an electron” is a localized excitation of that field: a ripple, a disturbance, a concentrated bundle of energy in the electron field.

The electron doesn’t move through the field like a boat through water. The electron is the field, locally disturbed.

Same for photons: they’re excitations of the electromagnetic field. Same for quarks, neutrinos, the Higgs boson—every fundamental particle is really a localized disturbance in its corresponding field. You are made these exact same fields.

This isn’t just philosophical reframing. It’s forced on us by the mathematics, and it has measurable consequences (antimatter, particle creation, vacuum fluctuations). But for our purposes, the key point is what it does to the double-slit experiment.

Why this dissolves the mystery

A field doesn’t move. A field just is—it has values everywhere, and those values evolve in time according to the field equations.

When we say an “electron” approaches a barrier with two slits, what’s really happening is this: the electron field has a localized disturbance (a concentrated ripple of energy), and as time progresses, the field’s configuration evolves. The values at each point change according to the field equations—equations that are modified by the presence of the barrier (a “boundary condition”).

The slits aren’t openings that the field “passes through.” They’re boundary conditions. The barrier constrains the field (say, forcing it to zero there), and the slits are regions where that constraint is absent. The field equations, subject to these boundary conditions, determine how the disturbance evolves.

As the field evolves, the disturbance spreads. On the far side of the barrier, the parts of the disturbance associated with each slit overlap and interfere. Where they’re in phase, the field amplitude is large. Where they’re out of phase, they cancel. This creates the characteristic interference pattern.

Interference isn’t mysterious for fields. It’s the most basic thing fields do. We don’t find it strange that water waves interfere, or sound waves, or light waves treated classically. The electron field is no different—it’s just that we’re used to calling localized disturbances “particles” and then getting confused when they behave like waves.

The real question

So fields interfere. But according to what rules, exactly?

In flat spacetime—the spacetime of special relativity, without gravity—we know the rules with extraordinary precision. Quantum electrodynamics, the quantum field theory of electrons and photons, matches experiment to ten decimal places. It’s the most precisely tested theory in all of science.

But spacetime isn’t flat. We live in a universe where mass curves spacetime, where clocks tick at different rates at different heights, where rotating bodies drag spacetime around with them.

How does curvature modify the equations governing field propagation? What observable consequences follow for interference experiments?

This is the domain of quantum field theory in curved spacetime—and it’s where our paper lives.

The Unfinished Revolution

Our paper works in a “semiclassical” regime.

To understand why we’re working in this “semiclassical” regime, it helps to see the bigger picture of 20th-century physics.

Einstein was centrally involved in three of the four foundational theories of modern physics: special relativity (1905), general relativity (1915), and quantum mechanics (through his work on the photoelectric effect and stimulated emission, even though he later grew skeptical of the theory’s completeness). The fourth pillar—quantum field theory—emerged from the work of Dirac, Heisenberg, Pauli, Feynman, Schwinger, Tomonaga, and others.

Here’s a remarkable fact: quantum field theory wasn’t invented from scratch. It was forced on us by trying to combine special relativity with quantum mechanics.

When Dirac tried to write a (special) relativistic wave equation for the electron in 1928, he found himself driven to an equation with strange features—including negative energy solutions that initially seemed like mathematical embarrassments. Those solutions turned out to predict antimatter: the positron, discovered in 1932.

More broadly, you simply cannot build a consistent theory of a fixed number of relativistic quantum particles. Special relativity allows energy and mass to convert into each other (E = mc²). Quantum mechanics allows fluctuations. Put them together, and you’re forced to allow particle creation and annihilation. A single electron can briefly conjure an electron-positron pair out of the vacuum, which then annihilates back. The number of particles isn’t conserved.

This means you can’t just do quantum mechanics of particles—you need quantum mechanics of fields, which can have any number of excitations. You’re driven to QFT not by choice but by logical consistency.

The expectation for the next step

Given this history, the path forward seemed clear. We combined quantum mechanics with special relativity and got quantum field theory. Now combine quantum field theory with general relativity, and surely we get... quantum gravity?

Decades of brilliant effort have been poured into this problem. The result: no complete, experimentally confirmed theory. Or as I like to say, the very technical term for this is: “bugger all.”

The technical obstacle is that general relativity, treated as a quantum field theory, is “non-renormalizable”—infinities appear in calculations and can’t be systematically controlled. String theory, loop quantum gravity, and other approaches offer possible resolutions, but none has made testable predictions that have been verified.

This is, to put it mildly, frustrating. We have two extraordinarily successful theories—quantum field theory and general relativity—each confirmed to remarkable precision in its domain. Yet combining them fully remains beyond our reach.

The “semiclassical” compromise

What we can do, rigorously and precisely, is something more modest: treat spacetime as a fixed classical background—but curved according to Einstein’s equations—and quantize the matter fields living on that background.

This is “quantum field theory in curved spacetime.” It doesn’t ask how quantum matter affects spacetime geometry (or asks only perturbatively, which means treating the back-reaction as a small correction to the background geometry). It takes the geometry as given and asks: how do quantum fields behave on a curved stage?

This isn’t the final answer. But it’s a mathematically well-defined framework, and it makes genuine predictions.

What the semiclassical approach has given us

This framework has produced some of the most striking results in theoretical physics:

Hawking radiation: Black holes aren’t perfectly black. Quantum field theory on a black hole spacetime predicts that black holes emit thermal radiation at a temperature inversely proportional to their mass. Black holes have thermodynamic properties—temperature, entropy—a discovery that’s reshaped our understanding of gravity, quantum mechanics, and information.

The Unruh effect: An observer accelerating through empty space sees a thermal bath of particles, where an inertial (inertial means not accelerating) observer sees only vacuum. The vacuum state itself is observer-dependent as is the notion of a “particle.” In other words, a acclerating observer will see a “bath” of particles (with a calculable distribution) whereas, in the same patch of spacetime, a non-accelerating observer will see only the vacuum.

Cosmological particle production: The expansion of the universe can create particles from the vacuum. Rapid expansion during inflation may have generated the density fluctuations that seeded galaxy formation.

These aren’t speculative ideas—they’re mathematical consequences of applying quantum field theory to curved spacetime. (Whether we can test them directly is another matter; Hawking radiation from astrophysical black holes is far too faint to detect.)

Our paper extends this framework to interferometry: what are the precise gravitational phase shifts in a double-slit experiment? It’s not quantum gravity, but it’s exact work at the interface of quantum mechanics and general relativity—and it yields concrete numbers.

Gravity Enters the Picture

How does gravity affect interference? There are two regimes to consider.

Uniform gravitational fields

In a uniform gravitational field—a good approximation near Earth’s surface over small distances—the main effect is straightforward: the two paths through the slits experience different gravitational potentials.

The interference pattern depends on the relative phase accumulated by different parts of the evolving field. Near Earth’s surface, proper time elapses faster at greater heights—a clock upstairs ticks slightly faster than one downstairs. The part of the field disturbance at higher elevation accumulates phase at a different rate than the part at lower elevation. This gravitational time dilation produces a phase difference that shifts the interference fringes.

This is called the COW effect, after Colella, Overhauser, and Werner, who first measured it in 1975 using neutron interferometry. The effect is substantial: for thermal neutrons, the gravitational phase shift is on the order of 100 radians (1 radian = 360 / (2 Pi) degrees). Large, unambiguous, experimentally confirmed. It’s been replicated and refined many times since.

Modern atom interferometers routinely measure gravitational effects. They’re used for precision gravimetry, tests of the equivalence principle, and searches for gravitational waves. The uniform-field gravitational phase is not exotic—it’s established physics.

Tidal effects—the next frontier

But gravity isn’t really uniform. The gravitational field varies from point to point. Its “gradient” matters.

In general relativity, the local variation of gravity is encoded in the Riemann curvature tensor—the mathematical object that captures how spacetime curvature changes from place to place. These “tidal” effects are what you feel when you’re stretched by a black hole’s gravity: your head and feet experience different pulls.

In an interferometer, tidal gravity means the two paths don’t just experience different potentials—they experience different curvatures. This introduces additional phase shifts beyond the COW effect.

These tidal phase shifts are what our paper calculates in detail.

Frame-dragging

Near a rotating mass—like Earth, or a spinning black hole—something even more interesting happens. The rotation drags spacetime around with it, an effect called “frame-dragging” or the Lense-Thirring effect.

This twisting of spacetime introduces a new kind of phase shift, one with a distinctive signature: it depends oddly on the slit separation. If you flip the sign of the separation (swap the slits), the frame-dragging phase shift changes sign too. Static gravitational effects are even—they don’t care which slit is which. Frame-dragging is odd.

This gives, at least in principle, a smoking gun. If you could measure the odd-parity component of the gravitational phase shift in an interferometer, you’d have direct evidence of spacetime rotation—gravity not just curving space but twisting it.

What the Paper Does

Previous work on gravitational effects in quantum interference tended to focus on specific cases: massive scalar particles here, photons in the geometric optics limit there, electrons with spin corrections elsewhere. The treatments were scattered, and it wasn’t always obvious which results were universal and which were particle-specific.

In our paper, we treat all three cases—scalar fields (spin 0), photons (spin 1), and electrons (spin 1/2)—within a single framework using path-integral methods adapted from Stodolsky’s formalism.

The central result is a compact formula for the gravitational phase shift:

Let me translate. The phase shift depends on:

R₀ᵢ₀ⱼ: the relevant components of the Riemann curvature tensor—the tidal gravitational field

ℓⁱ: the spatial separation between the slits

λ: the de Broglie wavelength of the particle

α_spin: a small spin-dependent correction

The spin corrections turn out to be suppressed by a factor of (ℏ/mc)²—about 10⁻¹¹ for electrons. At leading order, scalars and photons have identical phase shifts. This makes sense: both follow geodesics determined purely by the spacetime geometry.

What about the numbers?

Earth’s surface (neutrons): The COW effect gives ~100 radians. Already measured.

Earth’s surface (photons): About 10⁻¹² radians. Far too small to detect.

Low Earth orbit, tidal effects (⁸⁷Rb atoms): About 2.7 × 10⁻²¹ radians. This is our headline number for what a realistic orbital experiment would face.

Low Earth orbit (photons): About 10⁻²⁹ radians. Hopelessly small.

Futuristic kilometer-scale space interferometer: About 10⁻⁷ radians. This would require maintaining coherence over a kilometer in space with ultra-cold atoms—far beyond current technology, but not obviously impossible in principle.

The pattern is clear: tidal gravitational phase shifts are many orders of magnitude smaller than the uniform-field effects we’ve already measured. They represent a frontier we cannot yet reach.

Why Measure What We Can’t Yet Detect?

This might seem like an odd enterprise. If the effects are 15+ orders of magnitude below current sensitivity, why bother calculating them?

Setting benchmarks

Knowing exactly what nature predicts—even for effects we can’t measure—has genuine scientific value. It tells experimentalists what the target is. As technology advances, atom interferometers improve, space-based experiments become more sophisticated, it matters enormously to know what signal you’re looking for and how far you need to push.

It also constrains future theories. Any proposed modification of quantum mechanics or general relativity must reproduce these predictions in the appropriate limit. The numbers aren’t just “too small to matter”—they’re boundary conditions on theory-building.

Testing the semiclassical framework

QFTCS is not the final theory. It’s a stepping stone—perhaps the last solid ground before the unknown territory of quantum gravity.

But it’s a stepping stone that has produced remarkable results: Hawking radiation, the Unruh effect, cosmological particle production. Each of these extends our understanding of how quantum mechanics and gravity interact.

Adding precision interferometry to this list strengthens the framework. It’s another domain where we can ask: what does QFTCS predict, exactly? And even if we can’t test it yet, we’re extending the regime where semiclassical gravity makes quantitative claims.

The gap is informative

The enormous gap between the COW effect (~100 radians) and tidal phase shifts (~10⁻²¹ radians) is itself scientifically informative. It quantifies how hard the next step is. It tells us we shouldn’t expect to detect tidal gravitational effects in quantum interference anytime soon—but it also tells us exactly what “soon” would require.

The Road Ahead

Experimental capabilities are advancing steadily, even if the tidal regime remains distant.

The Cold Atom Lab on the International Space Station has demonstrated Bose-Einstein condensate interferometry in microgravity, achieving coherence times of several seconds. Ground-based atom interferometers have reached acceleration sensitivities around 10⁻¹⁵ m/s². Optical clock comparisons have achieved 10⁻¹⁹ fractional stability, probing gravitational redshift with exquisite precision.

None of these reach tidal gravitational phase shifts as we’ve calculated them. But the trajectory is encouraging. Each generation of experiments pushes sensitivity further.

What would detection mean, if it ever became possible?

It would be a direct test of how quantum fields respond to spacetime curvature gradients—not just the gravitational potential, but its variation in space. The frame-dragging signature, if ever isolated, would be an unambiguous probe of spacetime rotation.

These aren’t tests of quantum mechanics alone, or general relativity alone. They’re tests of their intersection—the regime where both theories matter simultaneously. That’s precisely the regime where we understand least and need guidance most.

Closing Reflection

The double-slit experiment has been with us, in one form or another, for over two centuries. It keeps teaching us about the universe—not because it’s irreducibly mysterious, but because it’s such a clean probe of how waves propagate.

Once you understand that particles are really localized excitations of fields, and that fields naturally interfere, the experiment stops being spooky. It becomes a precision tool. And taking it seriously in curved spacetime—asking exactly how gravitational effects modify the interference pattern—reveals what our theories predict at the edge of their validity.

The effects are tiny. We may not measure tidal gravitational phase shifts in my lifetime, or perhaps ever. But the predictions are exact, derived from our best understanding of quantum fields and curved spacetime. That’s worth something.

Sometimes the value of a calculation is proving an effect exists, even when we can’t yet see it.

The Paper

This work appears as a chapter titled “Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime: An Introduction to Gravity’s Impact on the Double-Slit Experiment” in the edited volume Quantum Theory Meets Gravity - From Curved Spacetime to Black Hole Information, which I co-edited. The full chapter is available online here.

The complete book will be published soon—I’ll write more when it’s released.

My co-author on this chapter is Arie Kapulkin, to whom I’m grateful for a genuinely enjoyable collaboration.

The “Book”

Check out my book, The Science of Free Will, which applies physics to the oldest problem in philosophy. What is free will in a deterministic universe? And what does that mean for AI?

Hello there!

Havnt got to the end of the article but quick question is there a math- less approach to quantum mechanics for nubes book out there? I am a general surgeon practising in India and have an interest in quantum mechanics and spirituality/philosophy

By the way, I do enjoy reading your articles and the wide arcs they trace eg- why indians form 75% of the ceo population and why there are less accidents on Jaipur highway courtsey the Royal enfield mandir etc I do hope to migrate to the USof A sometime but when that will be I dont know

Exceptional piece on tidal gravitational phase shifts in quantum interferometry. The gap between COW effects at 100 radians and tidal contributions around 10^-21 radians really underscores how the semiclassical framework is pushign into territory where even future tech might struggle. I worked with some cold atom setups a while back, and maintaining coherence over meter scales was already brutal; the kilometer-scale space interferometer idea sounds wild but getting phase stability there seems almost impossible. What makes the frame-dragging signture especially intriguing is that odd-parity dependence on slit separation.